TOXIC SITES

Superfund History

Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA)

Also Known As -Superfund

- Hinckley, California “Erin Brockovitch”

- Niagara Falls, New York “Love Canal”

- Camp Lejune, North Carolina

- St. Louis, Kentucky “Valley of the Drums”

- Times Beach, Missouri

- Verona, Missouri

- Parkersburg, West Virginia

- Washington Works DuPont Plant, West Virginia

- Michigan “Cattlegate”

- St. Louis, Michigan “Velsicol Chemical Plant”

- North Memphis, Tennessee “Velsicol Chemical Plant”

- Toone, Tennessee “Hardeman County Dump”

- Memphis, Tennessee “North Hollywood Dump”

- Centralia, Pennsylvania “Centralia Coal Fire”

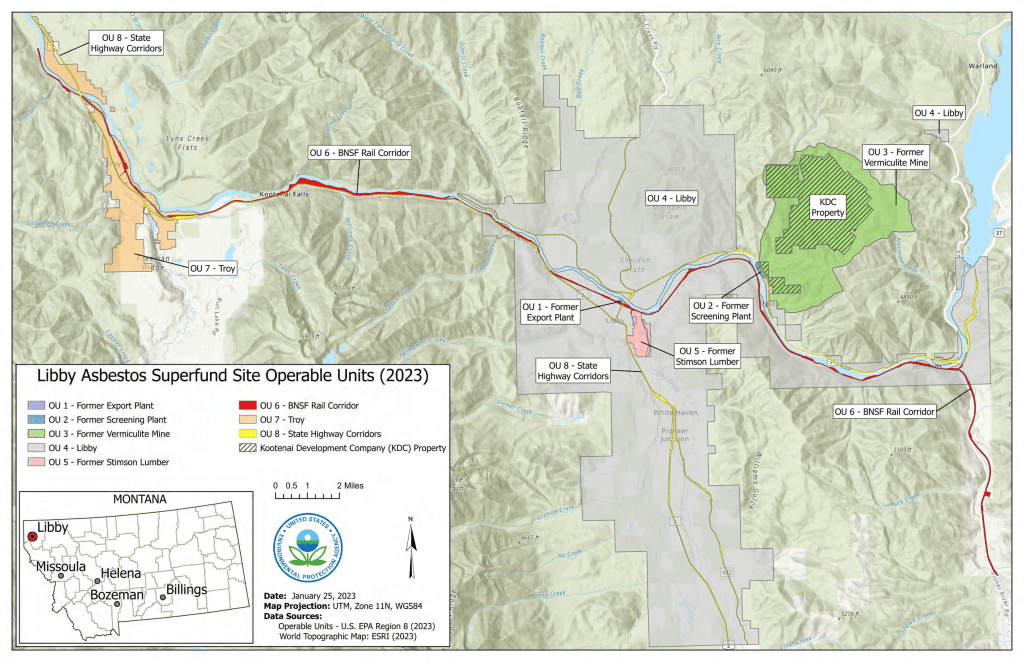

- Libby, Montana “Asbestos”

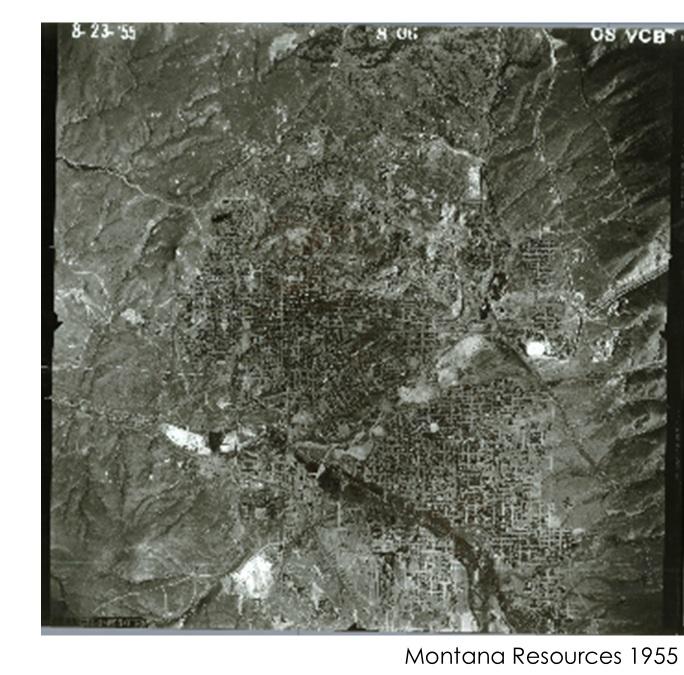

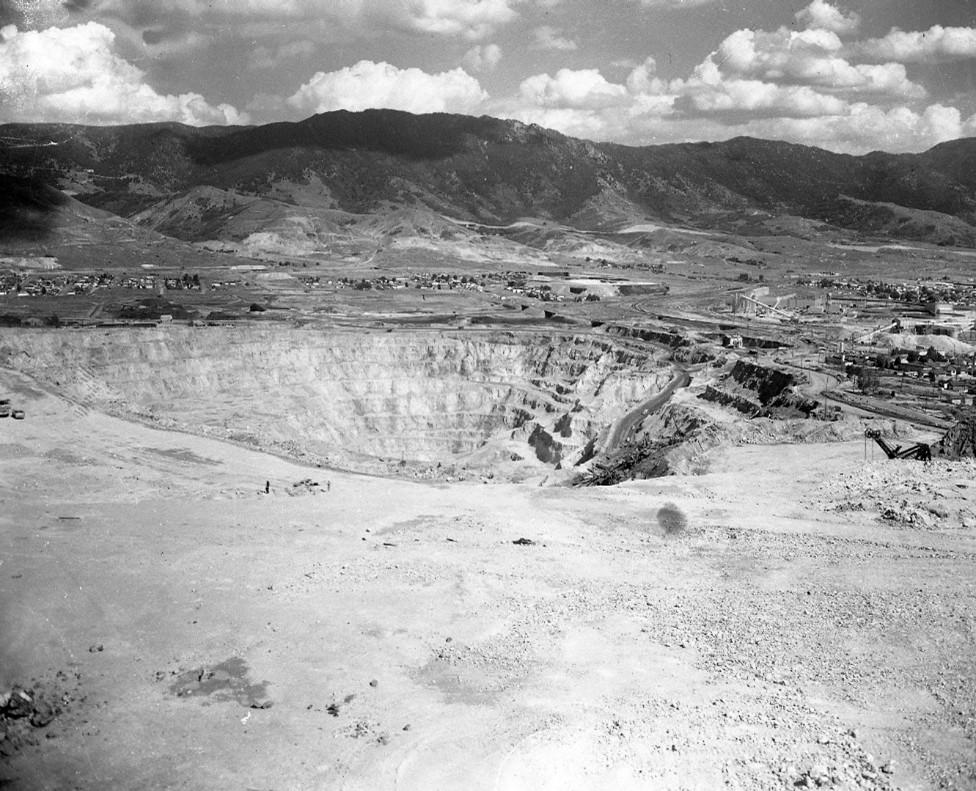

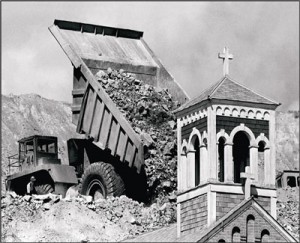

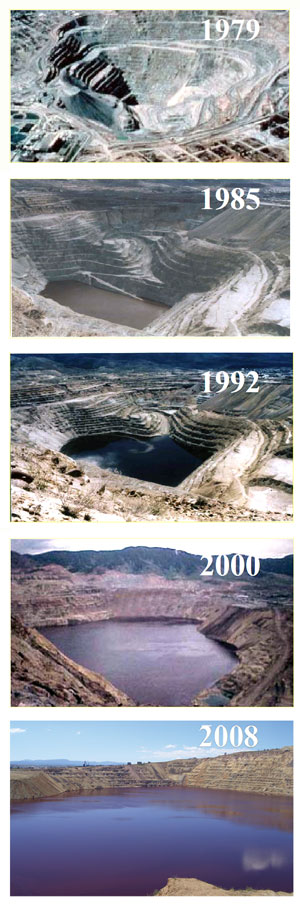

- Butte, Montana “Berkeley Pit”

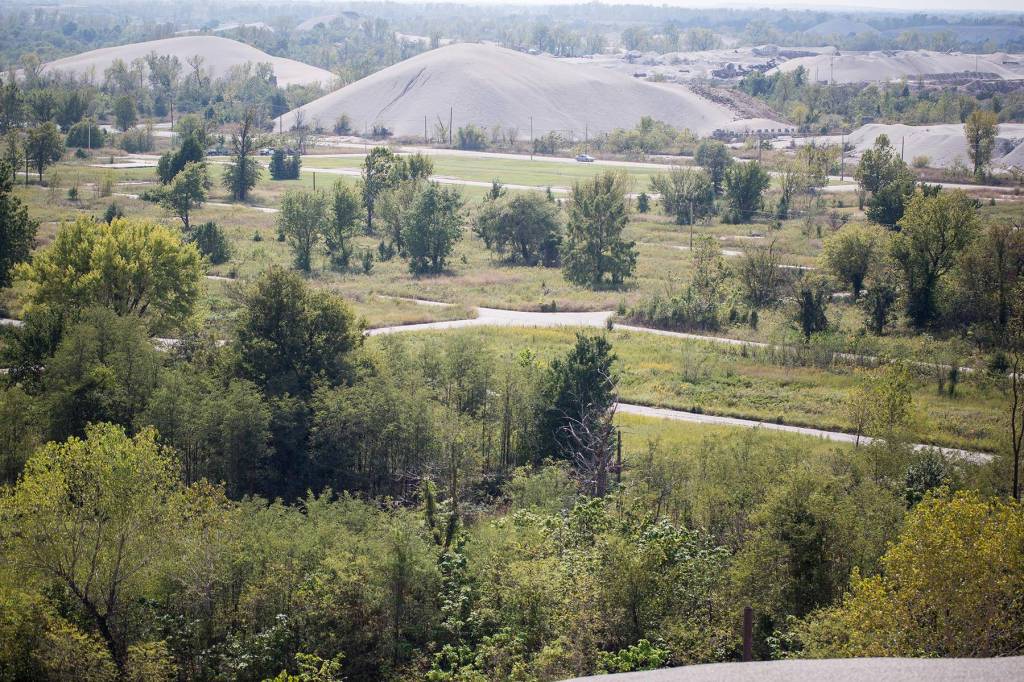

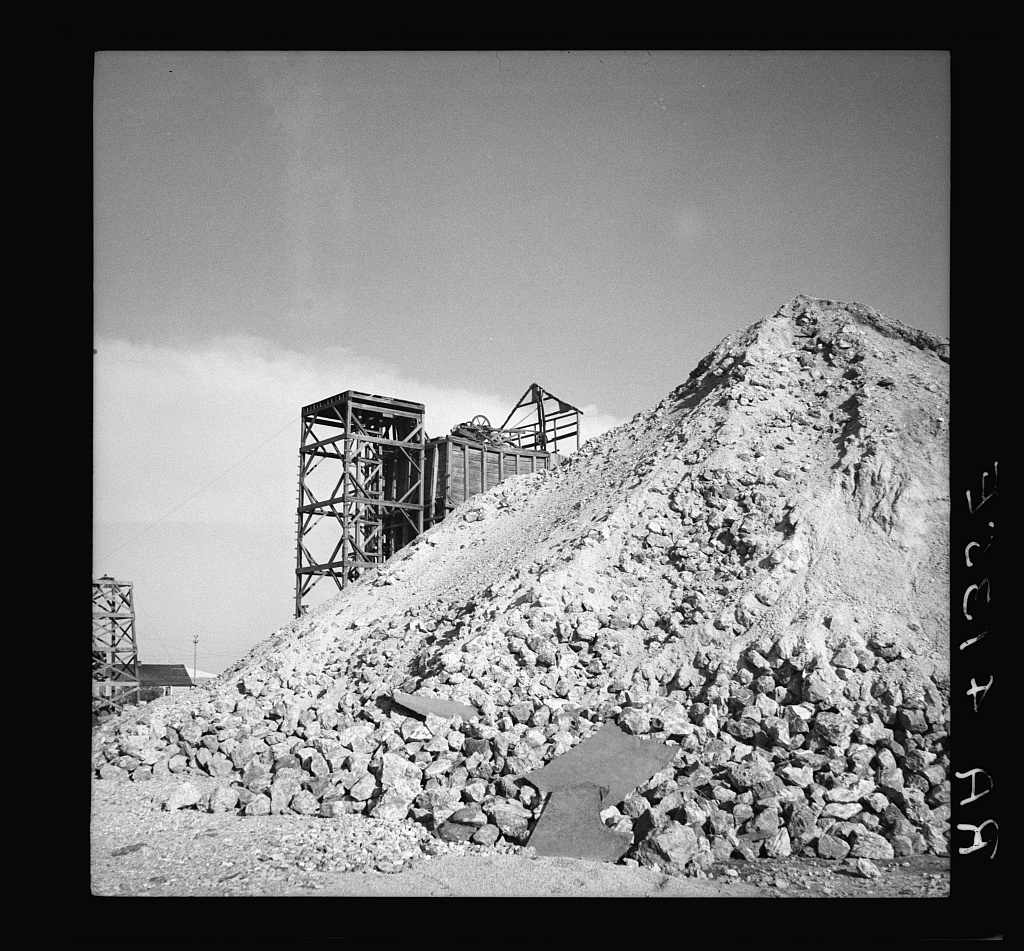

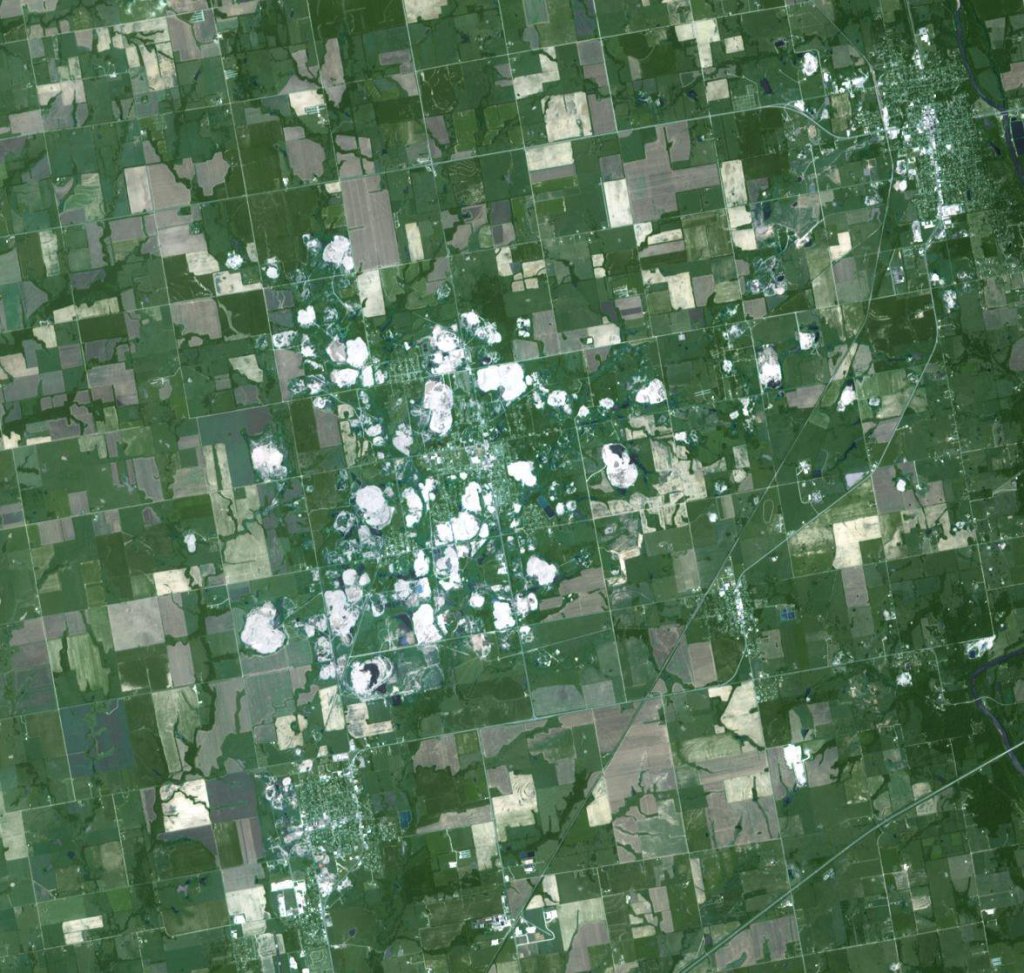

- Pitcher, Oklahoma “America’s Worst Environmental Disaster”

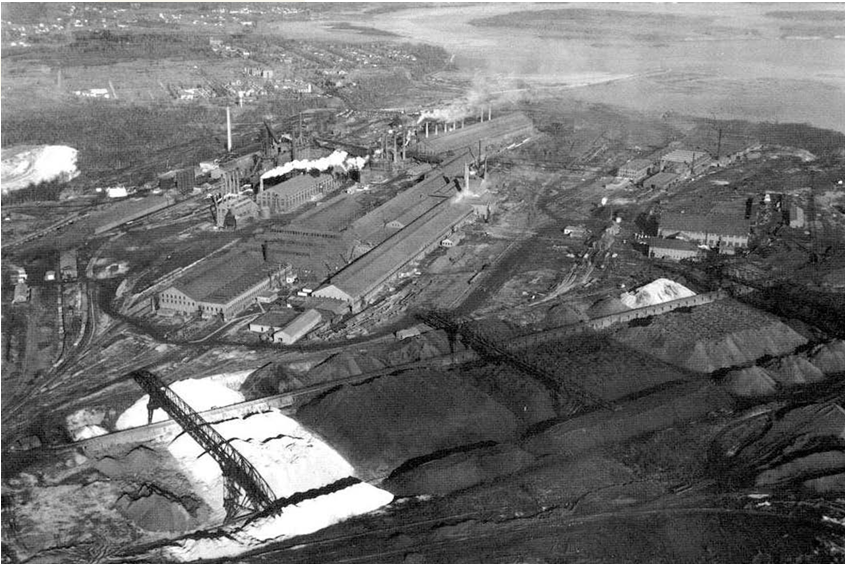

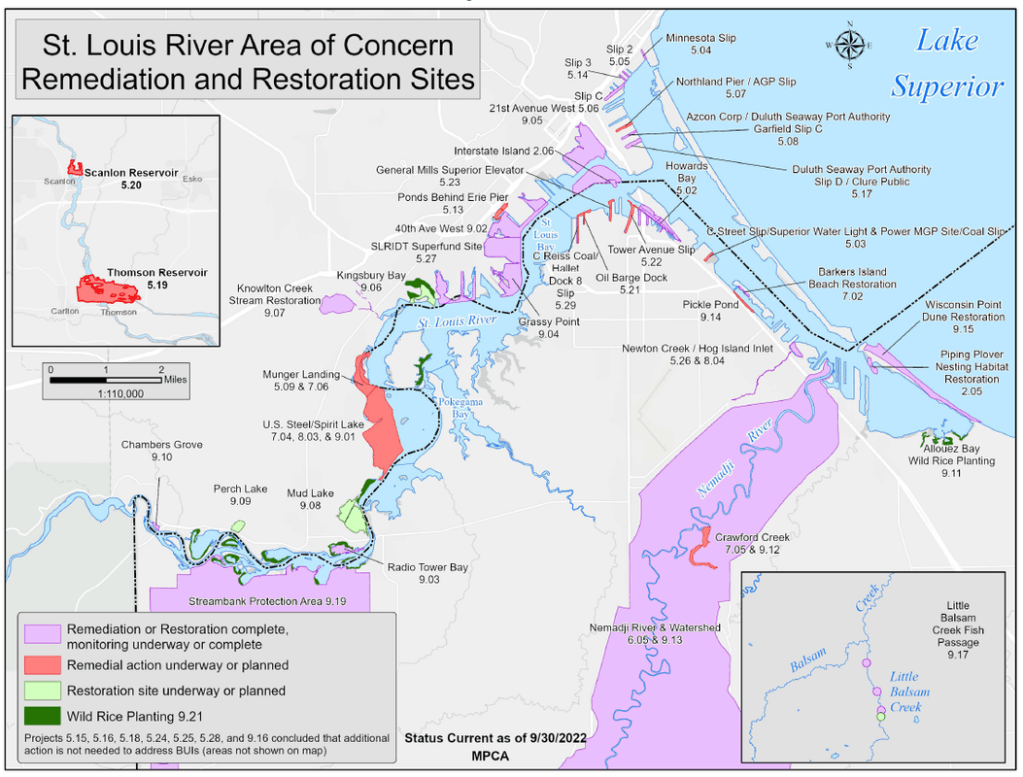

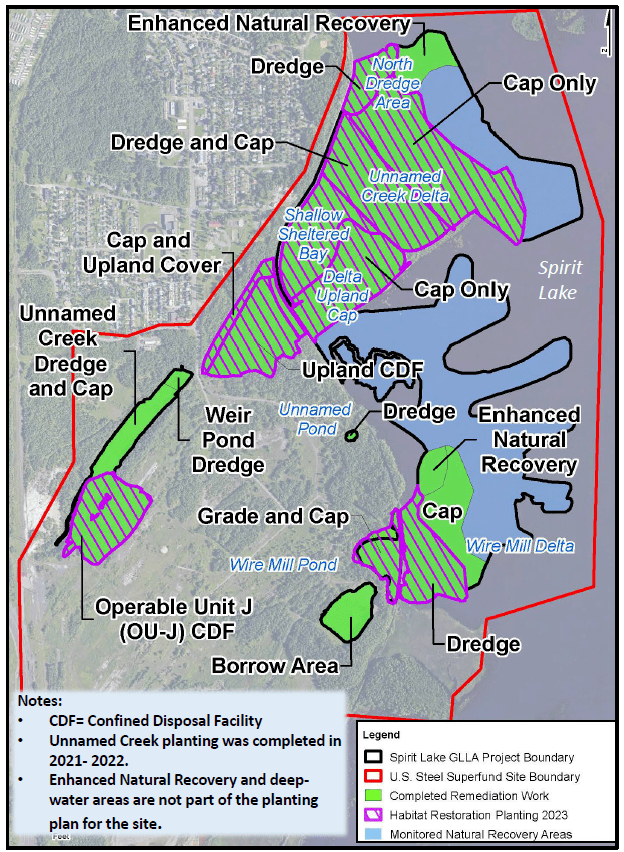

- Duluth, Minnesota “US Steel Site”

- St. Louis River Site “US Steel Site”

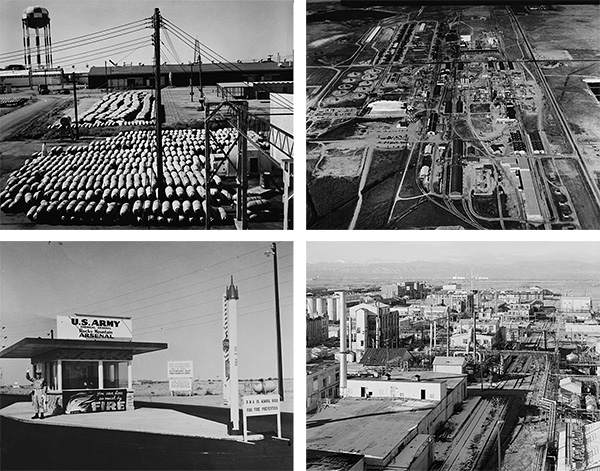

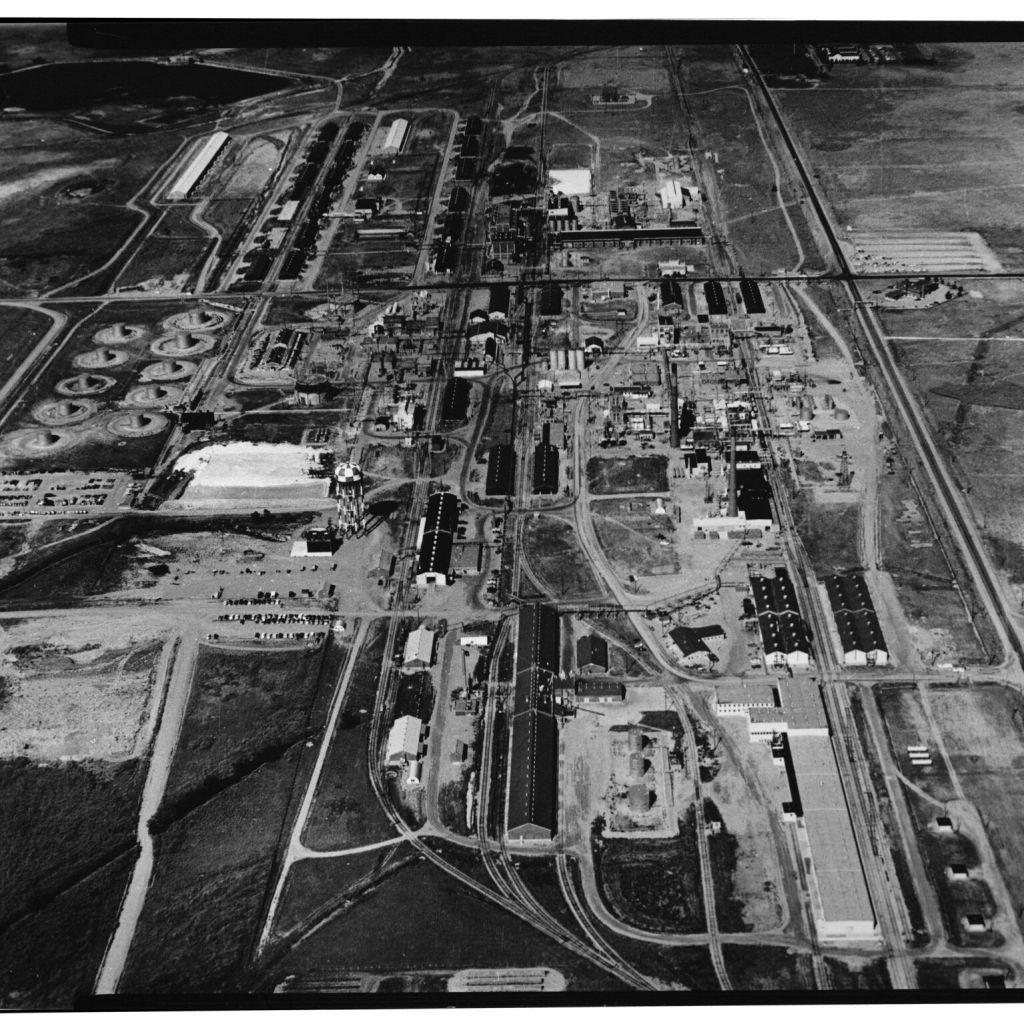

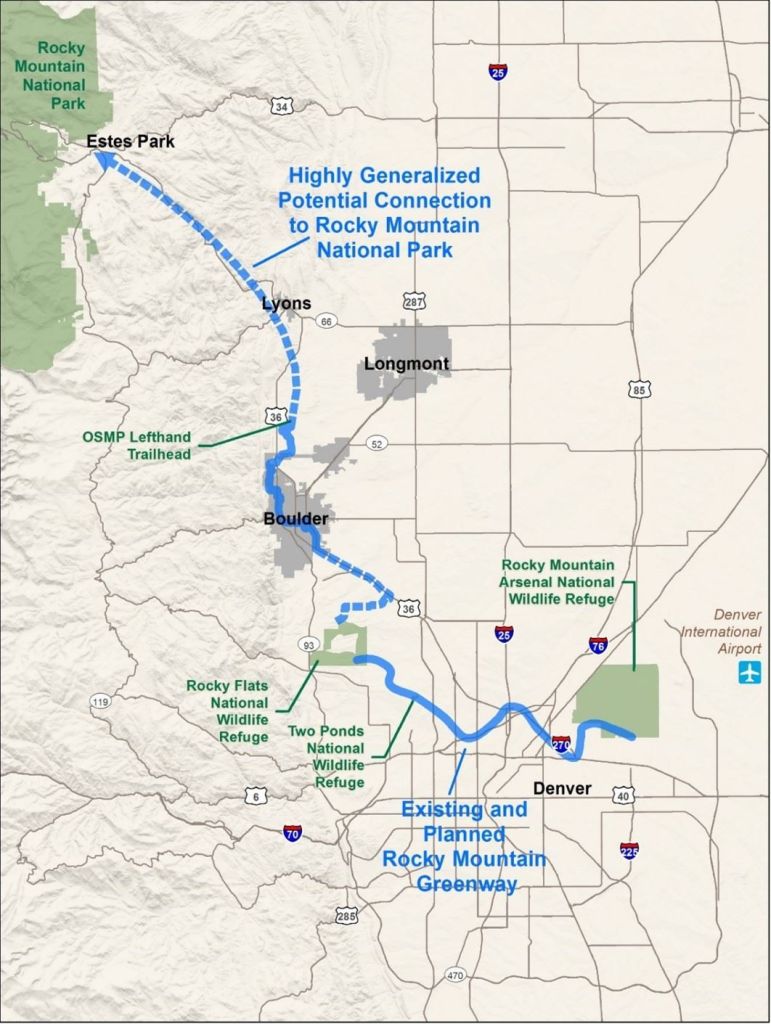

- Denver, Colorado “Rocky Mountain Arsenal”

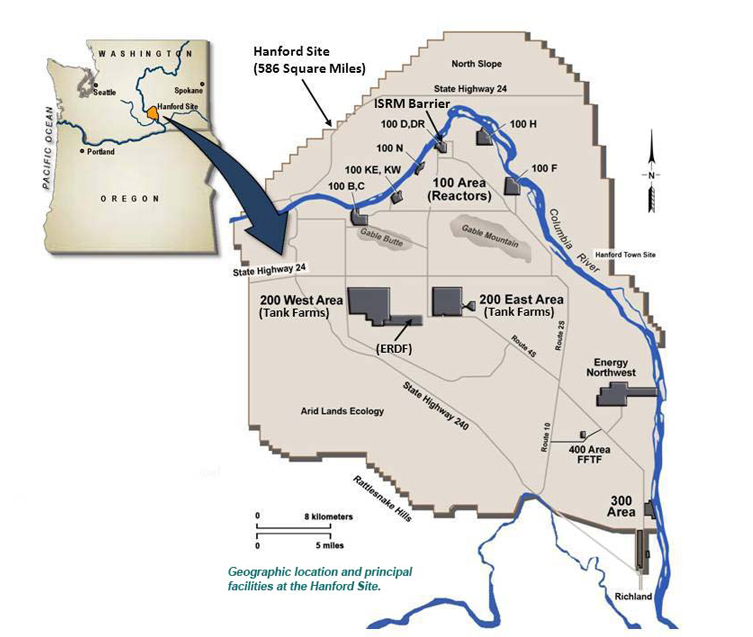

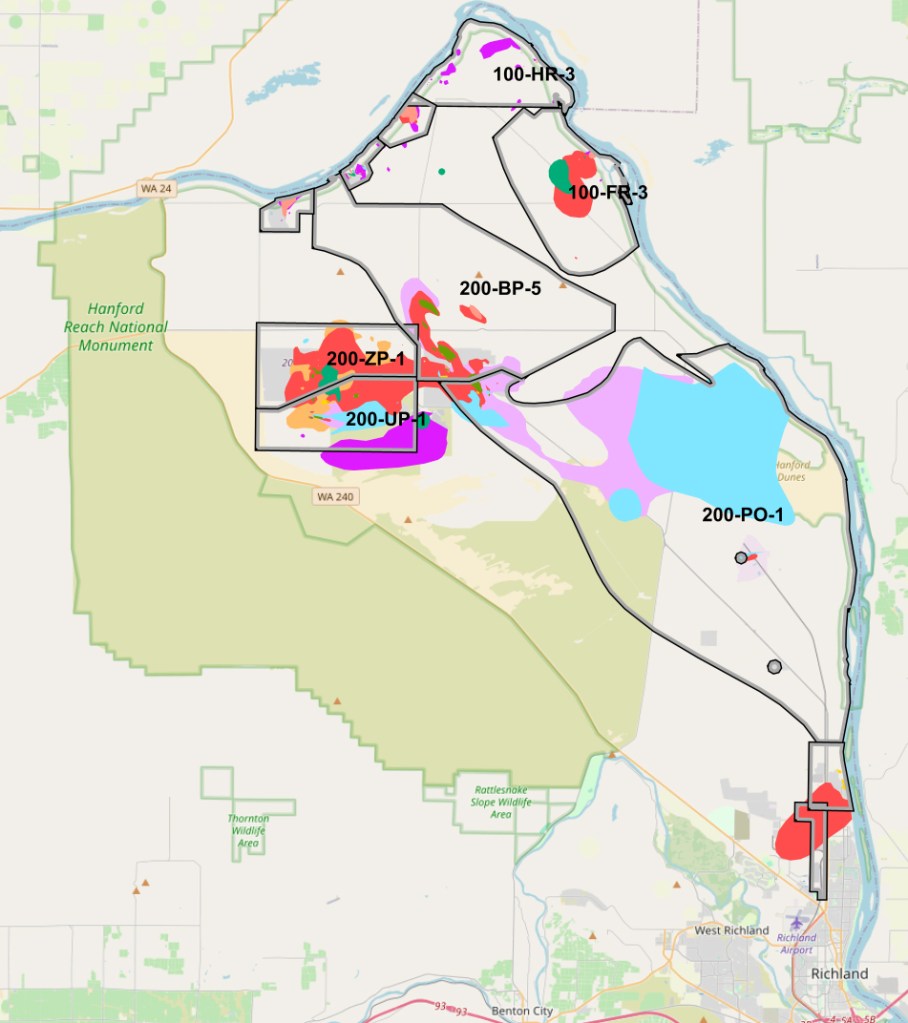

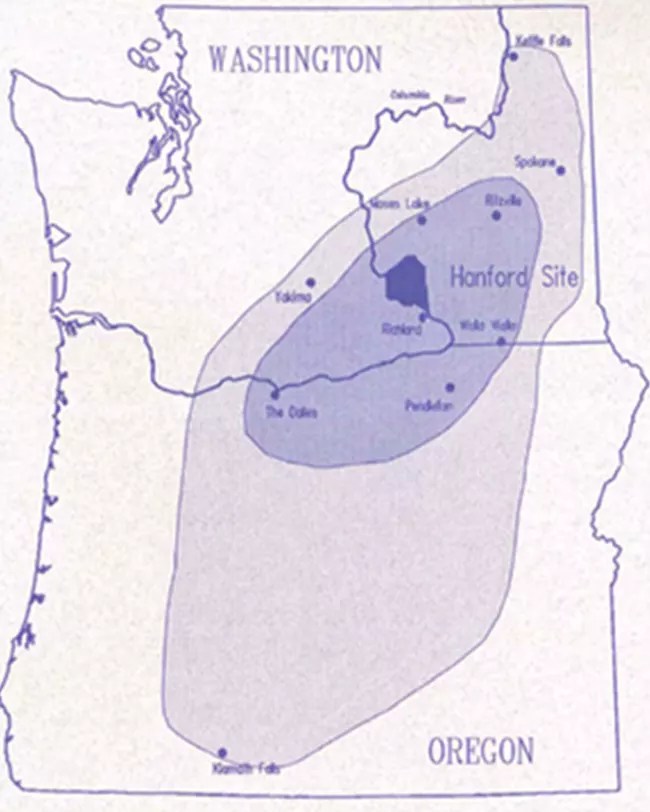

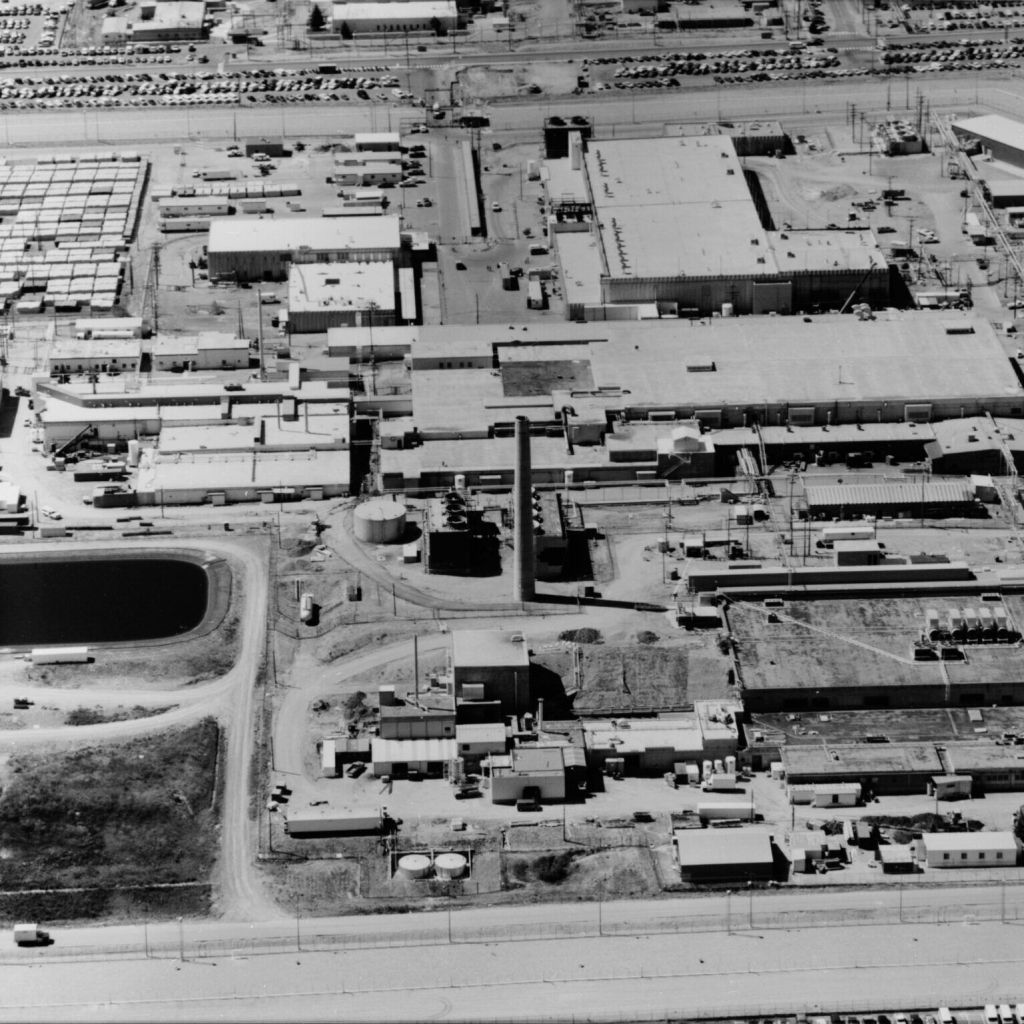

- Richland, Washington “Hanford Nuclear Site”

- Church Rock, New Mexico “Uranium Mill Spill”

- Gore, Oklahoma “Sequoyah Fuels Corp”

- Golden, Colorado “Rocky Flats Plant”

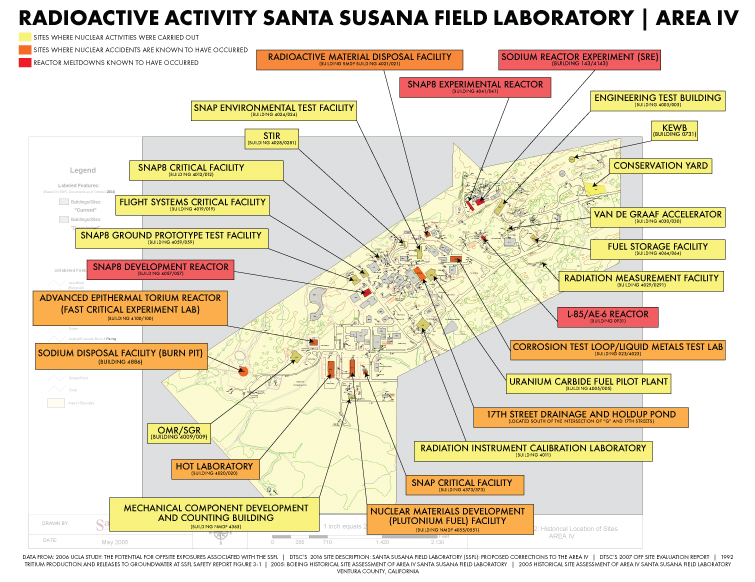

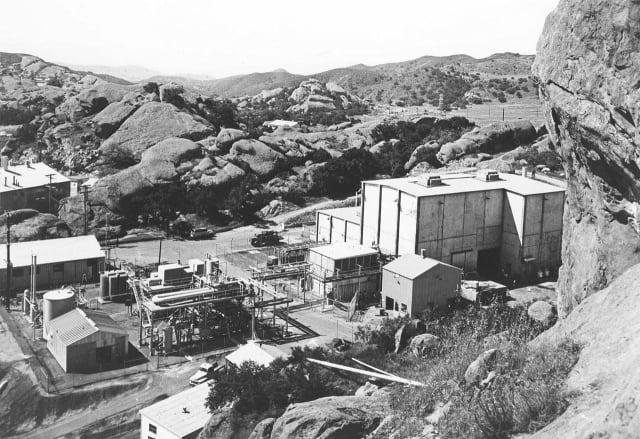

- Simi Valley, Santa Susana Field Laboratory

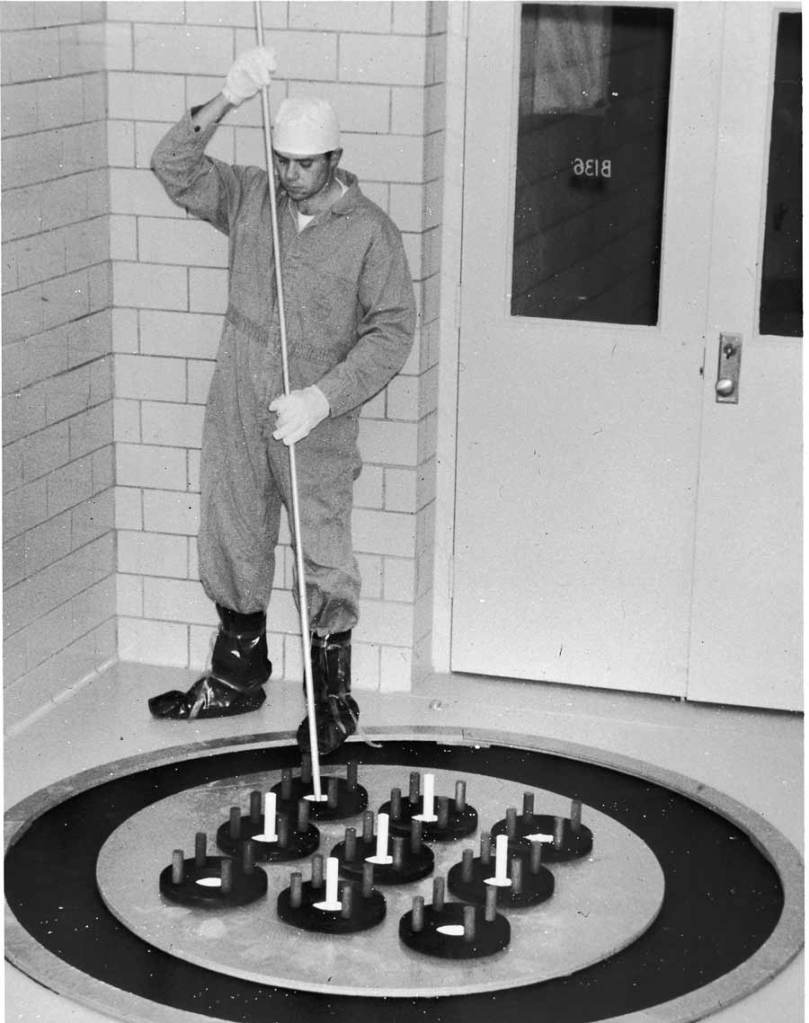

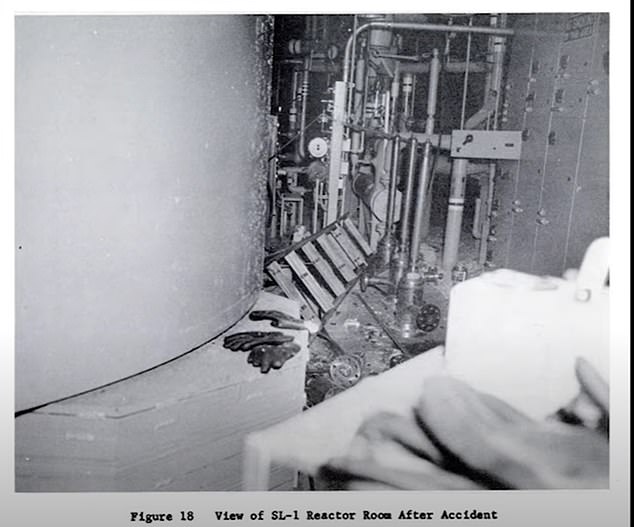

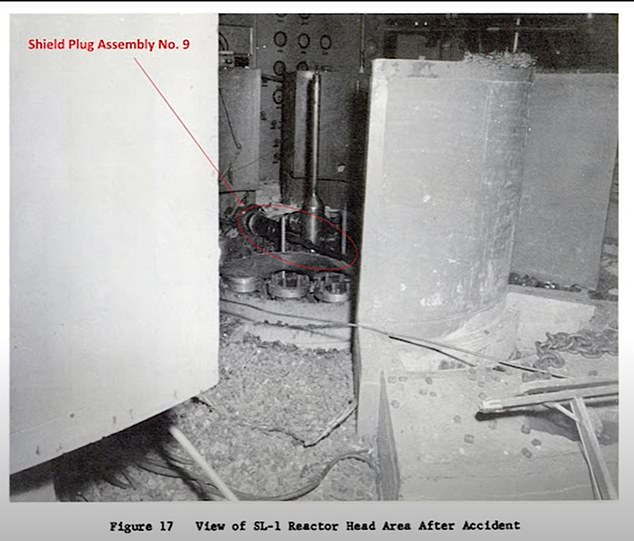

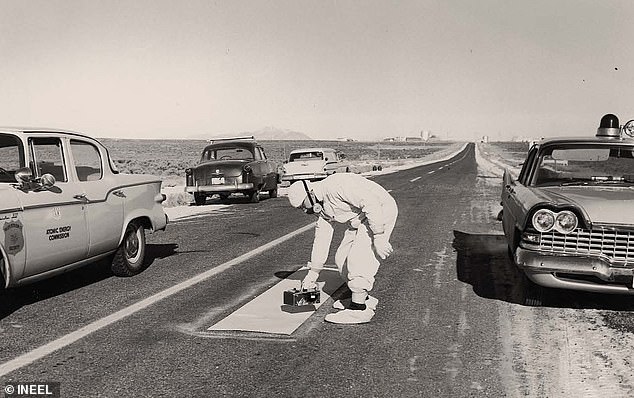

- SL-1 Reactor – Idaho Falls, Idaho

Courtesy of Erin Brockovich via ABC News

Groundwater Contamination

Hinckley, California

Erin Brokovich

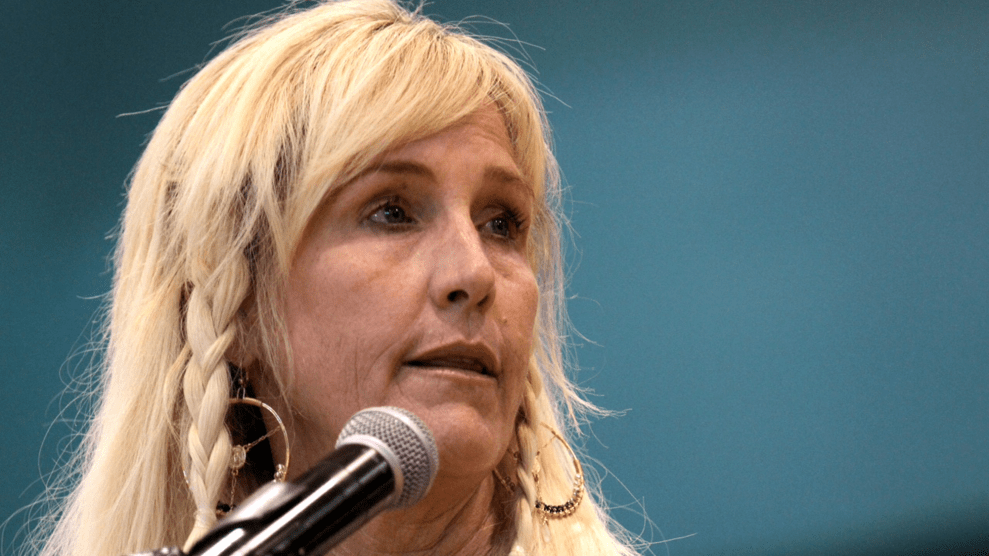

Erin Brockovich, for whom the Oscar-winning movie is named after, came to town from her life as a law clerk and single mother in Los Angeles in 1993, traveling three hours away to the town of Hinckley after hearing of the contamination. When she arrived she quickly found the water was lime green and eventually realized anything that dealt with the water was contaminated and sick; cattle with visible tumors, wildlife was missing, trees dying, the people had common nosebleeds, multiple miscarriages and cancer was common. She then started an investigation into the health effects of the contamination.

“Everywhere I was going in this little community, somebody had asthma, a complaint of a chronic cough, recurring bronchitis, recurring rashes, unusual joint aches, nosebleeds,” Brockovich told “20/20” in a new interview. “It didn’t make sense, and so the more I ask questions … the more I started to piece the puzzle together.”

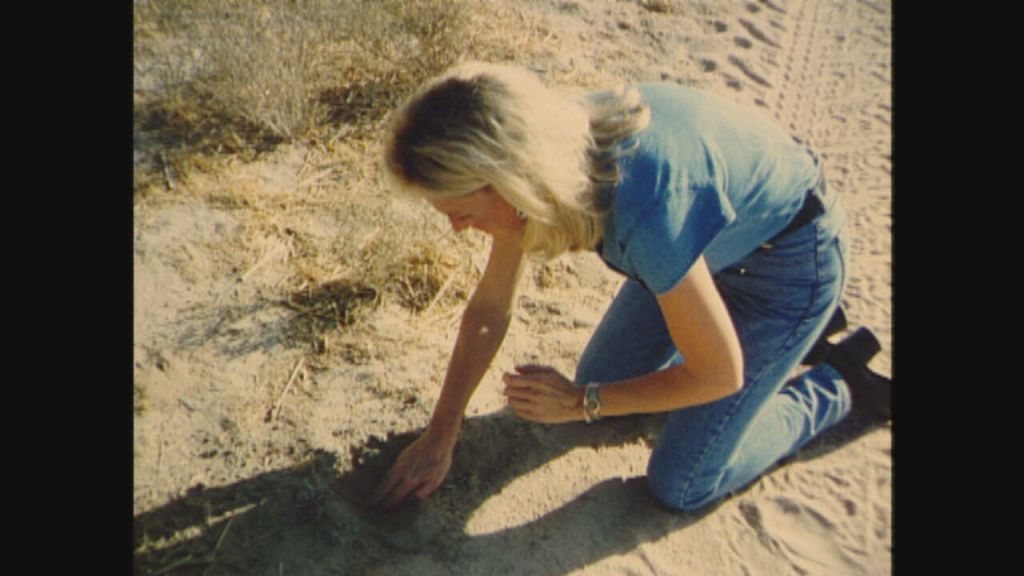

PG&E started adding a toxic form of chromium with water in 1952 to be used as rust preventative at a new pipeline pumping station. It wasn’t until December 7th, 1987 that the company would finally tell the local water board that the company had contaminated the underground water after claiming they discovered the problem on November 1987. The contamination reported violated the states legal limit, 50 parts per billion. It was Roberta Walker who finally had enough, collected documents including reporting in her diary that PG&E testing a monitoring well behind her home had a chromium 6 level of 4,900 ppb; she sent those documents to the law firm of Masry & Vititoe, where Erin Brockovich would take notice when they landed on her desk.

“Hinkley woke me up”, says Brockovich.

“Everyone said the two-headed frog and the green water was normal. I’m like ‘bullshit,’” she shouts in a way that those familiar with the film will recognize.

“Everything was off the charts,” Brockovich, 61, said in an interview. “Every single time one of these environmental disasters happens, its always a pissed-off mom that rises up. Starting with Roberta Walker. Every. Single. Time.”

The Pacific Gas and Electric company (PG&E) was dumping chromium-tainted waste water in unlined ponds, chromium 6 was used as a rust suppressor in the compressors for natural gas transmission lines. Chromium is a heavy metal that is rare in nature, it’s used in a variety of industrial processes, ranging from energy generation to steel making. It’s been labeled as an “emerging contaminant” by the Environmental Protection Agency, which means that the utility companies test for it but there aren’t any legal limits that they’re held to. A later study done by the US Geological Survey, that was ordered by the water board for PG&E to commission, showed that for years the company overestimated the amount of naturally occurring chromium in the ground and also underestimating the plume’s spread.

There was about 370 million gallons of waste water dumped into ponds around the town of Hinckley from 1952 – 1966. It wouldn’t be until December 1987 that PG&E would notify the water board of the contaminated water, that was measuring 10 times the state limit for total chromium.

The National Toxicity Program released a study in 2008 that found that the compound can cause cancer in rats and mice, there was a report on carcinogens in 2014 says “they are known to be human carcinogens.” A human carcinogen means that it’s scientifically proven to increase the risk of developing cancer in humans. The agency that oversees superfund sites, The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, has found chromium-6 to be “associated with respiratory and gastrointestinal system cancers.” The EPA, The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) have determined that chromium (VI) compounds are known human carcinogens, it can cause an increased risk of cancer as well as stomach, liver and kidney damage. It was also shown to cause lung cancer when inhaled by humans. Even in small amounts it can cause skin burns, complications during child birth, stomach cancer and pneumonia.

“There should be no carcinogen in water,” Dr. Lynn Goldman, former EPA assistant administrator of toxic substances under President Bill Clinton, told the PBS NewsHour. “The overall problem here is, what does it take for EPA to speed up its standard-setting process?”

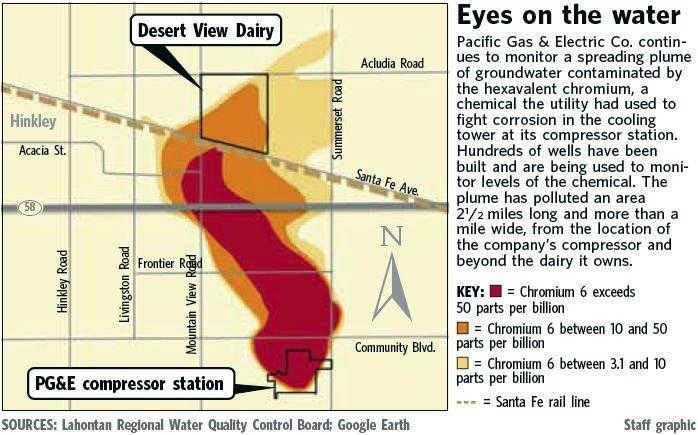

The plume, which is a body of contaminated ground water extending from a source of pollution, of chromium contamination has grown considerably over the years; starting from what was believed to be be 2 miles long and a mile wide plume, in 2008 it was shown to be spreading and in November 2010 PG&E was offering to purchase threatened homes and properties. The local water board reported in 2010 that the poisonous plume of chromium 6 was expanding despite their cleanup order 2 years prior, ordering PG&E to expand its monitoring of the water which just so happened to turn up contaminated areas that previously were assumed to be unaffected. The water board fined PG&E $3.6 million in 2012 for failing to contain the spread of the plume. By 2013 the plume was over 6 miles long, 2 miles wide and slowly growing.

Eventually there was a class action lawsuit against PG&E filed in 1993 which was referred to arbitration with maximum damages up to $400 million for more than 600 people; the first 40 residents were to receive $120 million. PG&E then decided to end arbitration and settle the case for $333 million; it ended up being the largest medical settlement lawsuit ever, now Hinckley is essentially a ghost town, but the effects on the people of this town and their health, can never be undone. In 2006 PG&E settled and agreed to another $295 million to settle cases against another 1,100 people statewide for hexavalent chromium related claims, in 2008 it settled the last of the Hinckley claims for $20 million. PG&E was served with an order to cleanup the effects of the chromium discharge in 2015 by the California Regional Water Quality Control Board, Lahontan Region. At the time of the report the plume was 8 miles long and 2 miles wide. The Lahontan Water Board has PG&E under orders to stop the expansion of the plume and cleanup the chromium plume.

Since the settlement in 1996, PG&E has been working on cleaning the tainted water and containing it, one of the ways they’re doing it is by injecting small amounts of ethanol into the groundwater to turn toxic chromium 6 water into less toxic Chromium-3 water. Chromium-3 happens to be a naturally occurring chemical and essential human nutrient, but we don’t differentiate between the two at the federal level, which needs to be addressed. As part of the mandated cleanup efforts by PG&E, water at 9 of the 44 wells tested were found to have chromium-6 levels more than five times higher than the states maximum, that’s not to mention it was 2,500 times higher than what the state deems safe for public consumption.

PG&E has more recently in 2024 pushed for a higher allowed limit of chromium-6 to be 9 parts per billion, by submitting a letter to the water board. It’s significantly higher than the currently allowed contaminant level, which is the strictest in the country but higher than was found in a 2023 study to be naturally occurring in the area. It’s estimated that to clean up the mess in the town it will take at least 150 years, while everyone in the deals with the side effects.

Chromium-6 has been found in lab tests to exist in the tap water from 31 of 35 American cities which was commissioned by the Environmental Working Group, it was found in concentrations above the safe maximum level that has been proposed by the California regulators. That leaves at least 74 million Americans in 42 states that drink tap water that’s polluted with chromium, the cancer causing hexavalent form is likely in much of that tap water. According to a 2016 analysis of federal data that came from drinking water tests conducted across all 50 states that showed hexavalent chromium contaminates the water supply of more than 200 million people, which is about 2/3rds of the entire population.

Public Health Assessment – 2000

US Dept. of Health and Human Services

Results of Hexavalent Chromium Background Study in Hinkley, California

Hexavalent Chromium Is Carcinogenic to F344/N Rats and B6C3F1 Mice after Chronic Oral Exposure

PUBLIC HEALTH GOALS FOR CHEMICALS IN DRINKING WATER -HEXAVALENT CHROMIUM

Hinckley Groundwater Remediation Program

Courtesy Mother Jones

Courtesy of Erin Brockovich

via ABC News

Courtesy of USGS

(David McNew/Getty Images) Courtesy LAist

Love Canal, Niagara Falls, New York

Before the State and Federal government got involved with the site, children would play in the material seeping up from the ground, completely unaware of the hazardous and dangerous fluid they were playing in. The EPA had announced results of blood tests in 1979 that showed high white blood cell counts, a pre-cursor to leukemia and also that 33% of the Love canal population had undergone chromosomal damage which looks worse when the average population experiences chromosome damage that only affects 1% of the population.

The Niagara Falls Board of Education purchased the canal in 1953 for a dollar but writes into the property deed a disclaimer with a limited liability clause of responsibility for future damages, in lieu of threat of eminent domain. The school board builds a school and sells land to be developed into residences, 23 years later in 1976 the Niagara Gazette reports stuff from the landfill is seeping into basements, a chemical analysis finds presence of 15 organic chemicals including 3 toxic chlorinated hydrocarbons that were all being moved through sewer city storm system and improperly discharged into the Niagara River.

The school was completed in 1955 and 400 children would start the school year in a new school, the schools architect wrote to the education committee stating workers found two dump sites with 55 US gallon drums containing chemical waste and noted it would be poor policy to build in the area without knowing what wastes were present and the concrete foundation might be damaged, that same year a 25 foot area crumbled and left toxic chemical drums exposed that filled with water during rainstorms and the kids would play in the puddles. The playground had to be moved because it was located directly on top of a chemical dump with the school construction being moved 80-85 feet to the north.

It was 1957 when the city of Niagara Falls thought it was a good idea while constructing sewers for new low income and single family homes to be built, to punch through the protective clay walls; the local government also had the bright idea to remove part of the protective clay cap to use it as fill dirt on the nearby 93rd street school. Between the school board knowing they paid a dollar for a property and that unknown chemicals may or may not be buried on the property, then built housing and schools for the families to be living all around a toxic waste dump and nobody thought twice? Was everybody involved in these decisions sharing the same 3 brain cells?

Courtesy Pop History Dig

There were 700 more families who had tests from the NYS Department of Health showing the toxic materials seeping into their homes, the federal government claimed they were at insufficient risk to warrant relocation; after another hard fought fight and protests from the activists Jimmy Carter declared a second state of emergency to relocate the reimagining 700 families, it probably led the federal government to quicker action when angry residents detained two representatives from the EPA as a form of protest to garner action and attention. President Carter signed a second state of emergency in 1981 after another hard fought battle by activists, the relocation costs for all families would be $17 million, even though the EPA had originally disagreed with the State of NY’s request to declare a broader emergency declaration area and the pace of relocation, stating the relocation was too hasty and the area was not as contaminated as the state claimed, the federal government has a history of denying events that it doesn’t want to acknowledge or pay for so who’s really surprised?

There were 2 more sites used for chemical waste dumping by Hooker Chemical, Hooker (S-area) was an 8 acre site which held 63,000 tons of chemical waste products and is located adjacent to the Niagara Falls drinking water treatment plant, as well as Hooker (102nd street) landfill which was 22 acres and used to dump 21,000 tons of mixed organic and/or inorganic compounds, solvents and phosphates, and related chemicals to include hexachlorocyclohexans which was used in a now banned pesticide, Mirex. Two of the other big selling chemicals were benzene hexachloride and trichlorophenol; lindane is a close relative of benzene hexachloride and are among the chemicals most commonly linked to Leukemia, lindane was eventually shown to accumulate in the brain and liver tissue and also damage the nervous system. Hooker would voluntarily withdraw its government registration for benzene hexachloride after lab tests in the mid 1970’s showed lab rats fed the chemical developed tumors and reproductive effects.

Courtesy of Levin Center

Camp Lejeune Water Contamination

Jacksonville, North Carolina

Camp Lejeune Timeline

History of the Contamination

Camp Lejeune, is a 156,000-acre (about 233 square miles) Marine Corps military base in North Carolina, home of the “Expeditionary Forces in Readiness,” had three contaminated water systems from 1953-1987 and is considered one of the worst toxic sites in the United States. Those sources were exposing over a million people to toxic chemicals that cause cancer, leukemia, birth defects and other serious health conditions. The three estimated contaminated drinking systems on base were Hadnot Point, Tarawa Terrace, and Holcomb Boulevard; the contaminates were from both off-site and on-site sources but most were sources on-site of the base. The contaminants ranged from pesticides such as chlordane and DDT, heavy metals like arsenic and lead, benzene as well as the solvents trichloroethylene, perchloroethylene (PCE), tests also found, Tetrachloroethylene (TCE), methylene chloride, vinyl chloride and toluene. Not to mention two different sites that contained radioactive material. There were so many babies that were born at Camp Lejeune that died in the 1960’s and 70’s that at a cemetery nearby there was a section that parents called “Baby Heaven”.

In 1963 the Navy’s Bureau of Medicine and Surgery issued detailed drinking water rules, banning any chemicals from being present in the water on military bases in concentrations that would jeopardize human health. Camp Lejeune officials were meant to enforce these rules at the base. The issues didn’t stop at mass contamination of water either, there also seems to have been some lack of care especially when they located a daycare in a former malaria control shop where pesticides were mixed and stored. That doesn’t even come to the level of a contractor getting ready to grade a parking lot and ends up digging up the radioactive bodies of dead beagles and laboratory waste labeled “radioactive poison”, strontium-90. This area was the former site of the Naval Research Laboratory dump and its associated incinerator. That wasn’t the only dumpsite for radioactive waste on the base though, retired Marine master sergeant Jerry Ensminger who spent 24 years serving this nation, he found a Navy document in 2007 that was from 1981 and indicated there was a dump site near a rifle range for radioactive waste that included two animal carcasses laced with strontium-90, it’s an isotope that causes cancer and leukemia. He also found other documents such as one that referred to “radiation pools”, there was also a 1984 water-testing report that showed radioactivity levels more than twice the allowed amount. Jerry sadly lost his 9 year old daughter in 1985 to leukemia, he later went on to found an advocacy group called The Few, The Proud, The Forgotten; they press the ATSDR, the Marine Corps and other government agencies to take action on the behalf of those affected by the contamination.

The residents of the base weren’t notified of the potential water contamination until a base newsletter in June 1984 stating the military was going to initiate a study on contaminants in the water, the announcement in the newsletter downplayed the exposure and the military didn’t even expect anyone to be exposed. The residents were then notified in December 1984 that their drinking water was contaminated with “traces” of contaminates, a few months later in April 1985 residents were notified there were 10 wells had been closed as a precautionary measure because “traces amounts” of contaminates in the water. This issue was only reported locally and those who had already left the base and the area weren’t notified, with most not learning of the issue until Dan Rather reported it in 1997- a decade after the last wells were shut down.

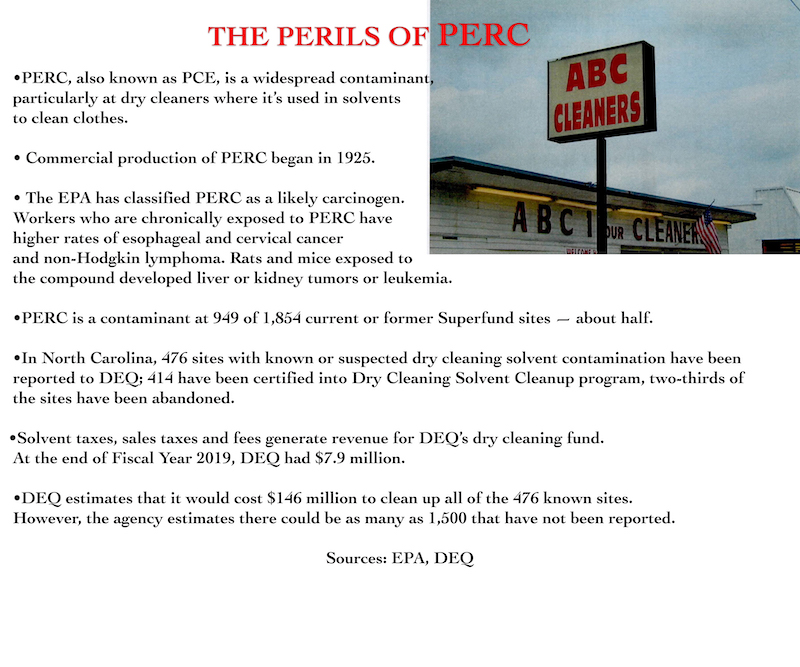

A family owned dry cleaning company, ABC One-Hour Cleaners, was a source of contamination whose building was located about two miles southeast of Camp Lejeune. They were illegally dumping a dry-cleaning solvent tetrachloroethylene (PCE) that was used as part of their operations, into the septic tank system which discharged to a drainage field on the property and also burying it improperly outside of the dry cleaning building. That’s not to mention the powder residue from solvent tanks, called “still bottoms” and also known as muck, would be used to fill potholes in the parking lot, about a ton over 30 years; a dry cleaner down the road paid for their still bottoms to be hauled to the county landfill. That chemical would contaminate two wells supplying water to one of the family housing communities on base, Tarawa Terrace.

After the EPA was created in 1970 waste disposal became more tightly regulated, the soil from under the building was tested showing PERC concentrations as high as 2,100 parts per million (ppm) while the groundwater at the cleaners was showing 12,000 parts per billion (ppb)- thousands of times higher than state regulations allow, groundwater is subject to stricter standards than soil, and it was located only 500 feet from Tarawa Terrace. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) conducted water modeling for the Tarawa Terrace and based on the model results, the PCE concentration was estimated to have exceeded the current EPA maximum contaminant level in the drinking water at the treatment plant for 346 months from November 1957 – February 1989 (almost 29 years).

The site was sold in 2005, changed names to A-1 cleaners and turned into a drop-off only location, they then shut down completely in 2011 and the buildings were demolished with the foundations being the only thing remaining. According to EPA documents the plume has grown to 1,500 ft long, 400 foot wide and as much as 250 feet deep in some places.

There was a feasibility study conducted by the EPA in 1992 and they selected the cleanup method in 1994; being implemented from 2000 – 2007 and involving a combination of a pump-and-treat method with monitored soil vapor extraction and natural attenuation (the reduction of the force, effect, or value of something). The contamination by 2009 had only been reduced by approximately 15%, in 2014 the EPA determined that that the only way to remediate the groundwater is they would have to address the soil contamination, they did so by removing the septic tank in 2019 and the soil cleanup was completed in 2020. The cleanup isn’t over unfortunately, it’s still going on according to the EPA, the area is surrounded by chain link fencing and under heavy restrictions. The original owners, now deceased, denied wrongdoing according to North Carolina Policy Watch.

There were multiple sources of contaminated water at some of the wells at Hadnot Point from on-site contamination including on-base spills at industrial sites, leaks from underground storage sites, leaks from drums at dumps and storage lots, an open storage pit, a former fire training area, an on-base dry cleaner, a liquid disposal site and a fuel tank sludge area. The Hadnot Point system’s primary contaminant was trichloroethylene (TCE), but there was also other chemicals found in the water to include benzene, methylene chloride, vinyl chloride and toluene.

Those weren’t the only things found in the water though, there were also metals that have been detected. The water treatment plant at Hadnot Point began operations in 1943 but there’s no estimates of when the contamination began. Hadnot Point had also supplied water to Holcomb Boulevard system from 1942-1971, which led it to be found to be intermittently contaminated. An Army laboratory chief who worked for the U.S. Army Environmental Hygiene Agency noted in 1980 that some chemicals were showing up in the water tests; “Water is highly contaminated with low molecular weight halogenated hydrocarbons.”. The lab chief, William Neal Jr., noted that the water at Hadnot Point was highly contaminated with halogenated hydrocarbons, which are chemical compounds that can include a variety of industrial organic compounds.

The base hired a contractor in 1982 to conduct similar tests looking for trihalomethanes (byproducts of chlorine), but he couldn’t accurately test for that because the water was too full of organic solvents, he was finding the halogenated hydrocarbons that was noted two years prior. Contractor, Mike Hargett, alarmed the base officials about the contamination but because there weren’t any defined standards for wastewater, little action followed; Hargett continued to speak out about the issue through 1983. Assistant Chief of Staff of Facilities got ahold of the state of North Carolina and notified them in May of 1988 there was a 15-foot thick plume contaminating the groundwater under the fuel facility. There weren’t any attempts to remediate it until 1989 even though a staff judge advocate had noted there was a loss of fuel at the rate of 1,500 gallons per month into the ground and observed the ongoing threat to human health.

There was also an industrial area at Hadnot Point that contained a fuel farm which had 14 underground tanks and a 600,000 gallon above-ground tank within 1,200 feet from a major drinking water well, HP-602. This information was revealed during the 111th Congress in September 2010 House hearing, it was also revealed that the Marine Corps knew about the contamination for more than 4 years before shutting down the drinking water wells at Camp Lejeune. There was a fuel leak in 1979, the first documented leak at the fuel farm when an estimated 20,000-30,000 gallons of fuel leaked from an underground valve. For years there was an estimated 1,500 gallons each month that leaked out of the fuel farm and the Marine Corps did nothing to stop it. A year later an engineer determined that the tanks were old and poorly maintained, with the storage tanks and connecting pipelines were corroded and deteriorating. The third contractor had a meeting in 1996, the minutes showed they estimated there was a loss of 800,000 gallons of fuel from the farm of which 500,000 gallons that was recovered.

The fuel leak itself in 1979 was never remediated, the deteriorating underground storage tanks were determined by the military that repairing the tanks would not be cost-effective and were not replaced until 1990, with a strange coincidence that the state of North Carolina has a statue of repose prohibiting lawsuits after 10 years, shocker. One of the wells tested so high for benzene it measured at 380 ppb, with the EPA having an established maximum contaminant level goal of zero parts per billion. A third contractor had “dramatically underreported” the level of benzene in the tap water on base, which was found by the Associated Press in 2012. The ATSDR found a contractor in 1984 has erroneously documented the benzene level in one well at 38 ppb, the final report by the same contractor in 1994 conveniently the benzene level altogether.

There were local requirements in 1979 that led the military to begin testing the water for trihalomethanes, a volatile organic chemical (VOC) that stems from water chlorination, the military tried to get an exemption from testing citing a lack of resources, it was denied. In October 1981 the military took samples and there were other VOC’s than the one they were testing for, there was tetrachloroethylene (PCE)- a dry-cleaning solvent, trichloroethylene (TCE)- a solvent used in metal degreasers, and benzene- a fuel component. TCE wasn’t regulated until 1989 and benzene wasn’t regulated until 1992 under the Safe Water Drinking Act, even though the health risk were known. The military ignored multiple warnings issues from the labs about the safety of the water.

Both the United States military and a privately owned dry cleaner were contributing to (or hid) the contaminated ground water. The water was impacted by the original base dump, leaks from underground drum dumps, leaks from underground storage tanks, transformer storage lot, open storage pits, the dry cleaner dumping waste, liquid disposal area, an industrial fly-ash dump, fuel tank sludge area, former fire training area and a burn dump.

When the testing of 40 wells started in 1984 by the military, there were 10 wells found contaminated with high levels of PCE and TCE, with all wells at Hadnot Point having traces of benzene. Those wells were removed from the rotation from November 1984 to February 1985 and Tarawa Terrae was closed permanently in 1987. The site wasn’t added to the EPA’s National Priorities List until October 4th, 1989, they found several contaminates of concern (COC) in the soil, sediment, groundwater, surface water of the base including but not limited to Dichloroethane, Tetrachloroethane, Trichloroethane, Arsenic, Barium, Bezene, Acetone, Vinyl Chloride, Chromium, Copper, Cyanide, Lead, Gasoline and Diesel. There was a Federal Facility Agreement (FFA) entered into by the Navy, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and the EPA in February 1991 for site cleanup activities. The contamination is so widespread across the base that there’s currently 40 Operable Units that are being investigated and remediated.

There was a study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that was published in the journal Environmental Health, it compared 150,000 Marines stationed at Camp Lejeune from 1975 – 1985 with 150,000 Marines stationed at Camp Pendleton in California during the same time. The results were that those who lived or worked at the base when the water was actively contaminated are more likely to die from Lou Gehrig’s disease or certain cancers. Camp Lejeune Marines were found to have the following increased risks; roughly 10% greater chance of dying from cancer, 35% higher risk of kidney cancer, 42% higher risk of liver cancer, 47% higher risk of Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and double the risk of ALS if exposed to vinyl chloride.

The cleanup process has included the Navy removing contaminated soil, above-ground and underground storage tanks, batteries, drums and other toxic waste materials from 1992-2001. Then from 2001-2009 the Navy had removed an estimated 48,000 pounds of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC’s) from the soil while they studied cleanup technologies, they added groundwater monitoring, used oxidants to break apart contaminants and included institutional controls. In 2009 the ATSDR removed the original 1997 Camp Lejeune Public Health Assessment have found that “that communities serviced by the Holcomb Boulevard distribution system were exposed to contaminated water for a longer period than we knew in 1997. Also, at the Camp Lejeune site, benzene was present in one drinking-water supply well that was not listed in the 1997 PHA. The PHA should have stated there were not enough data to rule out earlier exposures to benzene. We are currently studying that well to determine if it was used as a drinking water source while it was contaminated.”

The Navy inspector general produced an investigative report in 2013 obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request revealing “shortfalls in the oversight and management of drinking water for Navy personnel stationed overseas—even in wealthy, developed countries.” The report concludes that “not a single Navy overseas drinking water system meets U.S. compliance standards” or the Navy’s own governing standards,” according to POGO.

ATSDR Timeline

Agency for Toxic Substances

and Disease Registry

The Few, The Proud, The Forgotten

Clendening v. United States, No. 20-1878 (4th Cir. 2021)

Promises to Address Comprehensive Toxins

(PACT) Act

Janey Ensminger Act

Resources

Camp Lejeune Justice Act Claims

The Camp Lejeune Families Act of 2012 provided cost-free health care to veterans and their families who lived in the area exposed to the contaminated water with qualifying conditions such as;

- Esophageal cancer

- Breast cancer

- Kidney cancer

- Multiple myeloma

- Renal toxicity

- Female infertility

- Scleroderma

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Lung cancer

- Bladder cancer

- Leukemia

- Myelodysplastic syndromes

- Hepatic steatosis

- Miscarriage

- Neurobehavioral effects / Parkinson’s disease

Courtesy The Brockovich Report

Courtesy Kreindler LLP

St. Louis, Kentucky

Valley of the Drums

Courtesy Pop History Dig

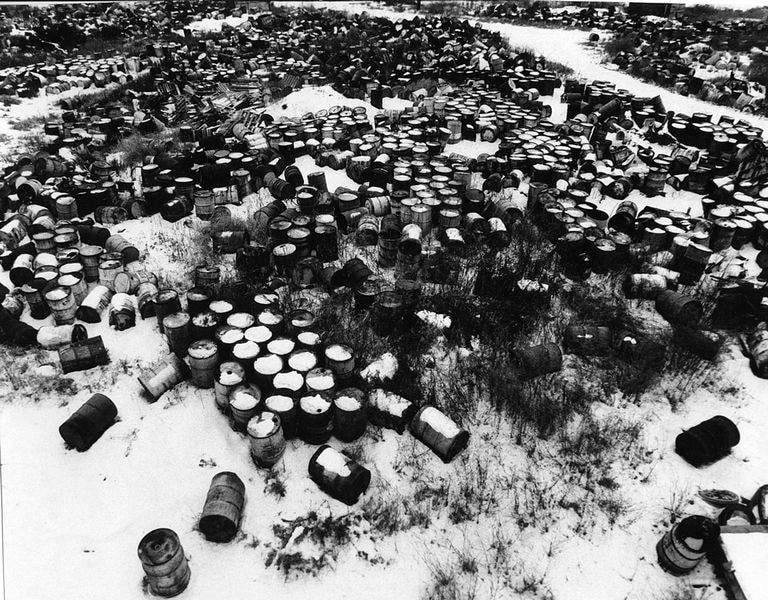

It was only in November 1966 when the industrial waste dump in Northern Kentucky caught fire that it was noticed, burning for a week and being visible in Louisville 15 miles away once the smoke drifted over the city is when people started to pay attention to what was going on. 23 acres, filled with barrels of various materials and open pits of discarded drums and waste. A.L. Taylor had some land and started a “drum cleaning” business and waste disposal business which really just meant dumping whatever comes through into open pits, a portion of which was paint but some of the barrels and drums found were from major companies such as DuPont, Monsanto, Ford Motor Co, Celanese Polymer Specialties Co, Ashland Chemical Co, Chevron Oil Co, Union Carbide and others.

Starting in 1967 and for the next decade A.L. Taylor was dumping waste in open pits and leaving other barrels to collect dust around his property, accumulating and/or processing tens of thousands of drums containing various degrees of paints, solvents and harmful chemicals. Since he never got the proper permits to run the type of business he was running, he was flying under the radar even with Kentucky environmental agency tried to bring legal action against him but the issue continued.

The EPA showed up in 1979 in response to a “surface water pollution emergency”, joining state regulators in removing 10,000 barrels of hazardous waste from the site and they weren’t the friendly kind you can jump on like in Donkey Kong Country. They didn’t do anything about other barrels and waste in a nearby forested hollow that became to be known as “gully of the drums”, 700 feet away from the landfill even though the court ordered the cleanup.

Courtesy Levin Center

Courtesy of Pop History Dig

Evacuation of Times Beach, Missouri

Bill Pierce/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

Courtesy of NPR

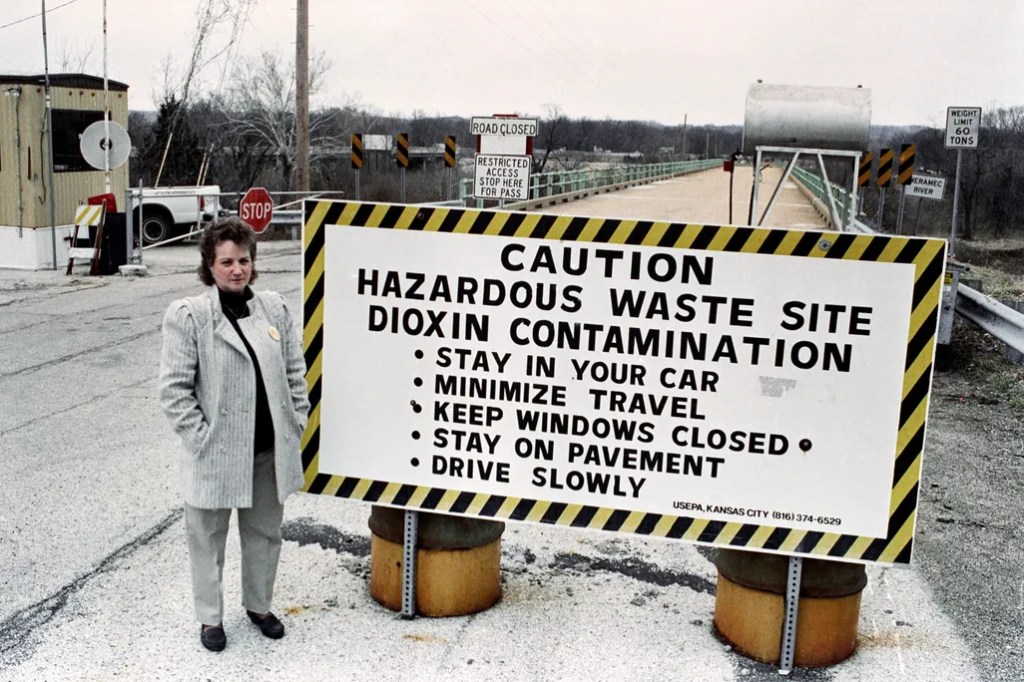

From 1971 – 1976 the town of Times Beach in Missouri was spraying oil on the dirt roads to keep dust down because they couldn’t afford to pave them, the spray was a mix of oil and chemical waste from production of a chemical for Agent Orange dioxin and hexachlorophene. Dioxin was added to the oil sprayed on the dirt roads and horse tracks around Missouri and it was the byproduct of the production of 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid by the chemical company Hoffman-Taff for Agent Orange and also the production of hexachlorophene by Northeastern Pharmaceutical & Chemical Company (NEPACCO) located in Verona, Missouri.

Courtesy of NPR

The site that first got the attention of the Missouri Department of Health and the Center for Disease Control in 1971 was at Shenandoah stables where over 40 horses died; birds, cats and dogs were also found dead near the arena, but when the stable owners 6 year old daughter became terribly ill it was when the investigation began. They eventually were able to track down the source to oil hauler Russell Bliss who sold the mix to towns, church’s and horse forms as a dust suppressant, he sprayed the oil mix around the area in the early 1970’s; it was sprayed in 25 locations around the state including the town of Times Beach, dirt roads, horse tracks and arenas.

The kids once had fun sliding in the purple tinted goo, but years later animals dropping dead and kids getting sick would change the perception of a veterinarian in the area. The CDC mobilized the resources in 1974 to investigate the contamination and where Bliss both stored and sprayed the oil dioxin mix. The EPA began testing in 1979 of the soil and in 1982 the agency announced that the levels of dioxin-the newspaper said is “the most potent cancer causing agent made by man” – were off the charts.

There was about to be a major flood in December 1982, a 500 year flood, the flood stage was 18.5 feet but the water crested around 43 feet; the Army Corps of Engineers had warned people the flood was coming and some stayed despite the warning. A few days after the city reopened it received the results of the soil test, the people of the town couldn’t afford to have the results quantified so they got a yes or no answer on PCB’s and Dioxin; the PCB levels were low but the dioxin was a problem. The EPA had a limit when this event happened of 1 parts per billion of dioxin and anything over would be hazardous, the town measured more than 100 parts per billion. Those who had returned were told to leave and the people who hadn’t come back yet were warned not to come back to town.

Photo Credit: Bettmann / Getty Images

The 2,500 residents were torn on whether to stay and rebuild or ask for an EPA superfund buyout, 50 of the 801 families in Times Beach wanted to stay and argued dioxin wasn’t a threat. The acting mayor then sent a petition to President Ronald Reagan for a request to have the EPA buyout property owners, in February 1983 the administrator of the EPA, Anne Gorsuch Burford, came to do just that, announce the buyout of the property owners at fair market value to the tune of a $20 million and another $15 million to build a concrete bunker to store the contaminated soil from 6 other sites would be stored. It was on April 2nd, 1985 that the towns former residents voted it out of corporate existence and only one elderly couple lived there at the time.

In 1990 the consent decree was entered and the EPA became responsible for excavation and transporting dioxin-contaminated soil from eastern Missouri sites to Times Beach for incineration, the state is responsible for long-term of the Times Beach site. The settling defendants were responsible for demolition and disposal of the structures and debris after the permanent relocation, the construction of a ring levee to protect an incinerator sub site from floods, the construction of a temporary incinerator, excavating the contaminated soils at Times Beach, operating the incinerator, and then the restoration of Times Beach upon the completion of the response actions.

The incinerator would end up treating a total of 265,354 tons of dioxin-contaminated materials from 27 eastern Missouri dioxin sites, including 37,234 tons from Times Beach after being brought to the site in 1996, with the EPA spending $250 million. The remains were then buried in a “town mound” and the cleanup was completed in 1997. It would be officially opened as a state park on the site of the 409 acre Route 66 Park, named after the historic road that runs through it, on the site of the former Times Beach in 1999 and in 2001 it was removed from the National Priorities List as it was no longer posing a threat to the public health or environment.

“Walking around the streets, walking into the houses, many of them were like people had just simply stood up, walked out and never came back. Plates on the tables, Christmas trees, Christmas decorations outside, and just street after street of that,” said Gary Pendergrass, a Syntex Corporation engineer hired to help clean-up Times Beach, as told to Jon Hamilton.

“This is one more example of the success of the Superfund program. Thanks to Superfund, Times Beach and the 27 nearby areas sprayed with dioxin-laden waste oil are clean and back in use,” said Lois Schiffer, former assistant attorney general in charge of the Justice Department’s Environment and Natural Resources Division. “Without the enforcement provisions of the Superfund law, we would never have been able to make those responsible for the awful contamination that occurred in and around Times Beach pay to clean it up.”

Courtesy of Smithsonian Magazine

James Denny Farm;

Verona, Missouri

The same company, Northeastern Pharmaceutical & Chemical Company (NEPACCO), whose chemicals were used in waste oil mixed dust-suppressant that was sprayed on roads and horse arenas across Missouri to include Times Beach; were found to have disposed of 80-90 drums of still bottoms and refinery waste in a shallow trench, which was roughly 10 feet wide and 60 feet long, on the farmland of James Denney beginning in 1971. A lawsuit was brought by the EPA in 1980 against NEPACCO, two of its former officers and an ex-employee; alleging a former shift supervisor, Ronald Mills, had a waste disposal agreement with NEPACCO and that supervisor paid a plant worker named James Denney to bury about 90 barrels of dioxin contaminated waste on his farmland, being paid $150 for use of his farm to dispose of the . The EPA wasn’t involved with the dioxin sites in Missouri until a former NEPACCO employee reported the toxic waste stored on a farm 7 miles from Verona, Misssouri.

The EPA wanted the defendant’s to pay for the other cleanup costs, as well as reimburse the EPA $500,000 it spent for the investigation and pinpointing the dioxin contamination at the Denney farm. EPA officials believe this was the first time a recovery suit brought under the 1980 Superfund hazardous waste cleanup had gone to trial as previously the EPA got reimbursed in negotiated settlements. The judge, Judge Clark, ruled that the EPA was only entitled for reimbursed for expenses after the clean up fund became effective in December 10th, 1980.

The company who leased the facility and equipment to NEPACCO, Syntax, was named in the suit and they made a consent agreement without admitting any guilt, agreed to clean up the site and reimburse the EPA up to $100,000 for the agency’s costs. Between October 1985 and June 1989 the EPA operated a mobile incineration system and treated almost 6 million kilograms of dioxin-contaminated wastes from 8 area sites. Let’s not forget that there were 37 dioxin toxic waste sites in Missouri alone.

Earl Tennant Farm,

Parkersburg, West Virginia

Wilbur “Earl” Tennant was a farmer in the 1990’s who was seeing his cows losing weight regardless of how much he fed them, developing tumors and dying; he contacted the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources and the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection but felt like they were stonewalling him, the state Veterinarian wouldn’t even come out to the property. He realized he needed help so he turned to lawyers in Parkersburg to sue DuPont and they turned him down as DuPont was one of the biggest employers in the area, neighbors helped remind him of a fellow neighbors grandson who was now an environmental lawyer in Cincinnati, so he reached out and got the help he was looking for; Rob Bilott, the environmental lawyer grandson of one of his neighbor.

The Tennants had sold some of their land to DuPont years earlier to be used as a landfill for office waste as DuPont told one of the brothers in person and also in writing, now the landfill that DuPont used was contaminating the creek that meandered past the landfill then spilled into his pasture, there was a drain pipe from the landfill into the creek on Earl’s farm. That same creek where Earls cows drank from, was covered in a foam recorded on a VHS videotape using a camcorder, the video starting with emaciated cows with tumors on their hides then showing the froth covered creek before cutting to a dissected calf with blacked teeth and oddly colored organs.

This would be a 20 year battle against DuPont by Rob Bilott, it would lead to the revelation that DuPont was dumping a chemical called C8 in to the Ohio river and the air around its plant and just what DuPont knew about what was going on. C8 or PFOA, has a related class of PFAS which is used in things like pizza boxes, flame-retardant foam sprays and Teflon; was dumped in to the river even though the company knew for decades that C8 was toxic and feared it was poisoning workers yet still continued to dump it with complete disregard for where it may go and who it may affect, they never told the EPA or the community about what they knew.

Earl Tennant would eventually agree to settle out of court with DuPont for an undisclosed amount of money.

When Ron Billot filed a suit in federal court, it was during litigation that it was revealed DuPont purchased PFOA from 3M to make Teflon, documents discovered confirmed DuPont knew about the potential health problems for decades and did nothing.

-In 1962, a rat study found “‘cumulative liver, kidney, and pancreatic changes’” in young rats dosed with PFOA.

-In 1965, a study on beagles exposed to PFOA showed toxic liver damage.

-In 1978, DuPont tested PFOA on monkeys. Monkeys given the highest dose died within a month, and even those given the lowest doses showed signs of toxicity.

-In 1978, after testing workers’ blood, 3M and DuPont decided not to disclose under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) the presence of fluorine found in the workers’ blood.

-In 1979, DuPont was aware that PFOA was biopersistent, and in 1980, DuPont had documentation showing they knew that PFOA bioaccumulated in the body.

-In 1981, a 3M study on rats showed PFOA caused birth defects, specifically to the eyes, in unborn rats. Unlike before, 3M disclosed the study to EPA. DuPont, studying their workers, noticed that two of seven babies born recently had been born with eye defects. DuPont did not continue the study. Another rat study failed to show the same defects and 3M went back to EPA and relayed that the previous study was invalid.

-In 1983, documents demonstrated that DuPont was aware of a viable, potentially less toxic, alternative, TBSA, as well as methods for reusing PFOA; however, these were more expensive and DuPont chose to proceed with the status quo.

-In 1988, a two-year cancer study on rats linked testicular tumors to PFOA.

-In 1988, DuPont scientists set a Community Exposure Guideline for DuPont workers with safe limits for PFOA at 0.6 ppb, around the lowest they could detect at the time.

-Also in 1988, DuPont decided to move thousands of tons of PFOA contaminated sludge to an unlined landfill, the landfill upstream of the Tennant’s farm.[2] Shortly after, DuPont measured the PFOA leaching from the unlined landfill into the creek at levels as high as 1600 ppb. DuPont did not warn the Tennants or the public.

-In 1993, another rat study linked PFOA to testicular, pancreatic, and liver tumors.

-In 1999, another monkey study showed monkeys with low doses of PFOA dying within a few months or suffering so much that the researchers “sacrificed” them.

(2)Robert Bilott, Exposure 81 (2019). DuPont was able to dump the PFOA sludge as nonhazardous waste because PFOA was not regulated under TSCA. PFOA and PFOS were grandfathered into the Act and companies only had to report if a chemical presents “a ‘substantial risk of injury to health or the environment.’” Id. at 94. DuPont did not self-report.

Throughout this period and for decades more, DuPont maintained that PFOA demonstrated no known human health effects.

STEEP

Sources, Transport, Exposure

and Effects of PFAS

Kentucky tests public drinking water systems, half of systems tested show evidence of PFAS contamination.

C8 Health Project

Mid-Ohio River Valley

DuPont experimented on “volunteer” employees by having them smoke cigarettes laced with Teflon

C8 Science Panel

According to a report by the CDC, 97% of all Americans were found to have PFAS in their blood

Forever Chemicals (PFAS) show up in your clothes, food and home

The Devil they Knew: Chemical Documents Analysis of Industry Influence on PFAS Science

PFAS is present in 98% of all Americans

Forever chemicals are everywhere

Perfluoroalkylated compounds in the eggs and feathers of resident and migratory seabirds from the Antarctic Peninsula

Alarming levels of PFAS in Norwegian Arctic ice pose new risk to wildlife

DuPont study confirmed PFOA is toxic in animals – 1961

List of nearly 800 hazardous substances subject to regulation

What EPA has learned about PFAS

-PFAS are widely used, long lasting chemicals, components of which break down very slowly over time.

-Because of their widespread use and their persistence in the environment, many PFAS are found in the blood of people and animals all over the world and are present at low levels in a variety of food products and in the environment.

-PFAS are found in water, air, fish, and soil at locations across the nation and the globe.

-Scientific studies have shown that exposure to some PFAS in the environment may be linked to harmful health effects in humans and animals.

-There are thousands of PFAS chemicals, and they are found in many different consumer, commercial, and industrial products. This makes it challenging to study and assess the potential human health and environmental risks.

DuPont Washington Works Plant

West Virginia

In the 1980’s the DuPont company thought it would be a an easy way to dispose of some waste and decided to dump 7,100 tons of PFOA-laced sludge into open unlined pits, which just so happened to then seep into the ground and get into the local water table that was used to supply drinking water to the 100,000 people in the towns of Lubeck, Vienna, Little Hocking and Parkersburg.

In the 1990’s and 2000’s the DuPont company decided to voluntarily test the water around certain company facilities in West Virginia, they ended up finding varying concentrations in and around certain DuPont facilities but also in private drinking wells and public water supplies.

The Chemours’ Washington Works plant still discharges high levels of PFAS, including banned PFOA and the new yet still toxic GenX, despite a 2023 federal order meant to curb pollution.

Stoneridge Farm PFAS Contamination

Arundel Maine

“Cattlegate”, Michigan

There was a huge problem that came to the herds of Michigan’s cattle farmers in the early 1970s, workers at the Michigan Chemical Company, owned by Velsicol Chemical Corporation, provided feed bags that would get sent to feed mills around the state, the issue is they had inadvertently switched the bags from those containing magnesium oxide, a common cattle feed supplement with other poorly marked bags of a known flame retardant containing polybrominated biphenyls (PBBs) as the main ingredient. The bags were then shipped to feed mills for use around the state of Michigan in the feed supply for cattle and other livestock, unknowingly leaving farmers to poison their animals, all because there was a shortage of pre-labeled paper bags and a communication oversight in the plant sending out the feed bags to the Michigan Farm Bureau Services building. It wasn’t just the bags that were contaminated, the machines used to mix the feed were also contaminated and kept spreading the toxic chemicals into the feed for months. By the spring of 1974 PBB’s were found in the food chain through widespread farm product consumption of pork, lamb, chicken, beef, milk, chicken and eggs. Michigan Chemical and the Farm Bureau had put together a $15 million insurance pool to help farmers that lost their herds and the herds production but the damage wasn’t done.

Photography by Mark Brush, Michigan Radio

Courtesy Emory University

The first person to do an investigation in 1973 to the sick cows was 31 year old dairy farmer Frederic “Rich” Halbert who happened to hold a master’s degree in chemical engineering and also used to work for Dow chemical company, after veterinarians couldn’t find out the problem and with the sick cows not eating much and the milk production dropping from 13,000 lbs to 7,600 lbs a day, he thought it might be the feed. His vet, Dr. Ted Jackson, would end up being a major ally in the fight, he had noticed some other symptoms in the cattle, they had runny eyes and stopped chewing their cud (portion of food regurgitated in order to digest a second time), the udders on cows who recently gave birth were shrinking, So he fed a group of calves feed from half a dozen different sources and he was able to figure out the source of the problem was a product purchased from Farm Bureau Services Inc., earlier that year. Frederic ended up spending $5,000 of his own money on lab tests and long distance phone calls to find out the feed had been contaminated with PBB’s after his herd was quarantined he ended up having to destroy 800 of his cows in 1974.

It was on April 19, 1974 that Rich got an answer from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Center, a low-resolution test on a mass spectrometer, the mystery chemical was a form of bromine. By the time it was discovered what was causing a state wide cattle illness nearly all living Michiganders, 9 million people, had consumed the chemical through meat or milk, which was later found to be linked to high levels of exposure to breast and liver cancer, as well as kidney and thyroid problems. There were tens of thousands of animals began dying, giving birth to young with gross deformities, losing their ability to walk straight and shaking uncontrollably.

Emory University has done PBB studies with the Rollins School of Public Health to understand the effects on humans, Michele Marcus, has been studying the effects PBB contamination for the last 15 years. As a Rollins environmental epidemiologist, she knows that even now, 40 years after the accident 80-85% of Michiganders have elevated PBB levels in their blood, if that wasn’t bad enough animal studies have shown it can have affects several generations later. The state of Michigan Department Community of Health transferred the PBB registry to Rollins where Marcus heads up the research.

“We know from animal studies that some of these hormone disrupting chemicals can affect up to four and five generations down the line,” says Marcus. “But it’s one thing to be a scientist and study these statistics. It’s quite another to have a mother approach you and tell you her daughter entered puberty at age five.”

In total there were 32,000 cows, more than 6,000 swine, 1,370 sheep, 1.5 million chickens and 4.5 million eggs destroyed as a result of the contaminated feed, as well as considerable quantities of eggs, cheese, butter and dried milk over a two year period. There would be over 500 farms that would be quarantined across the state of Michigan due to PBB exposure and contamination. Since the contamination was discovered in 1974, both the Farm Bureau Services and the Michigan Chemical Company have settled 500 claims with farmers to the tune of $30 million, with some 300 other claims still pending. Farmers have maintained that state officials tried to coverup the scandal, with agriculture department officials contending that farmers were exaggerating the extent of PBB contamination and blamed it on poor livestock management by the farmers.

Serum Polybrominated Biphenyls (PBBs) and Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) and Thyroid Function among Michigan Adults Several Decades after the 1973–1974 PBB Contamination of Livestock Feed

Courtesy Birdge Michigan

Velsicol Chemical Plant

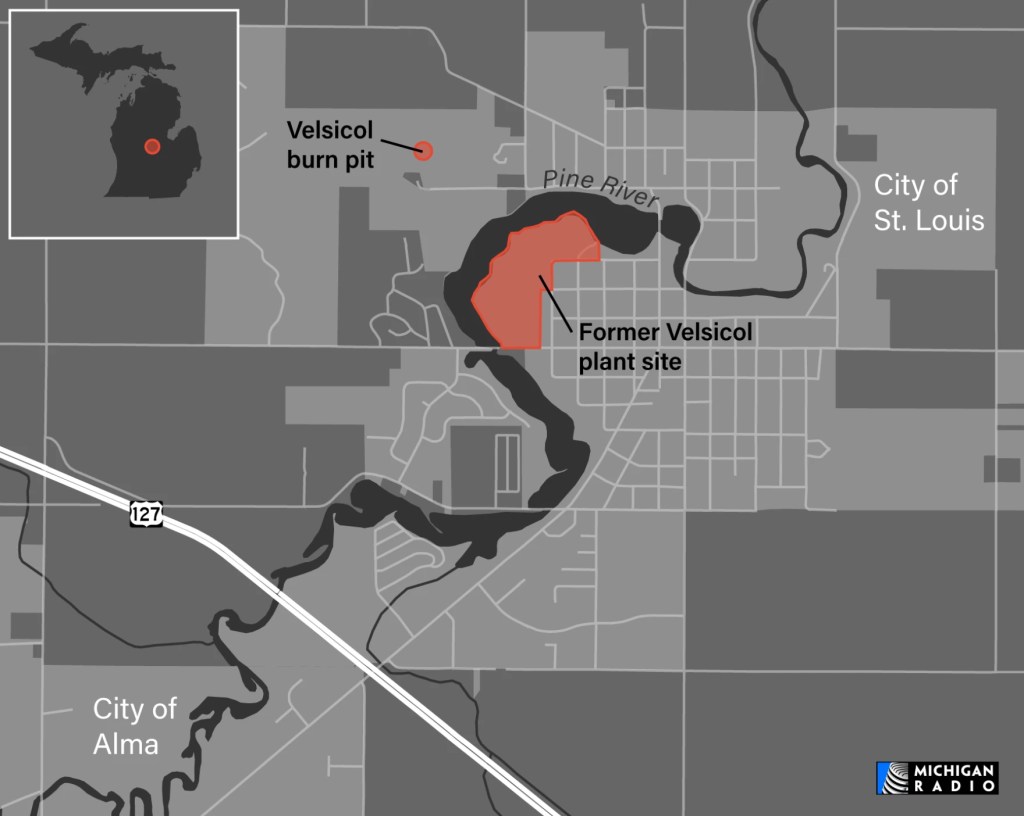

St, Louis, Michigan

Courtesy Tennessee Lookout

Velsicol Chemical Company, formerly Michigan Chemical Corporation, had a 54 acre main-plant site in St. Louis where they produced various chemical compounds from the 1930’s until it closed in 1978, to include the now banned pesticide DDT, cattle feed supplements, chlordane which was banned in 1988 because of its cancer risk and the flame retardant polybrominated biphenol (PBB). After contamination at the former plant site was discovered the building was simply knocked down and buried with hundreds of chemicals in 1982 in an agreement with the EPA and the state of Michigan, then there’s the significant contamination of Pine Creek that borders the former site on three sides. The EPA, Velsicol and the state of Michigan entered a consent agreement in 1982 where Velsicol agreed to construct a slurry wall around the former site and put a clay cap over it. In this time the town had to shut off their wells and switch to a new water supply, all thanks to this wonderful company.

There was an initial clean-up effort by Velsicol in the early 1980’s, originally thought to be good enough, the reality would be starkly different than the company hoped for, it was discovered later that the remediation efforts had failed when high levels of pesticide were found in fish tissue and river sediment, leading the state to issue a no consumption advisory for any fish species. The DDT levels in the fish have been reduced by over 98% which is a great start but the state plans to keep the fish advisory until the entire site has been cleaned up.

Velsicol filed for bankruptcy in 1999 and the EPA took control of the site and the remediation of not only the main plant site but also the Pine Creek and the Burn Pit area. The actions taken at the site from 1998 – 2006, addressed contamination in the Pine River at a cost of $100 million, during that same time period the EPA funded a sediment cleanup in the Pine River adjacent to the site, with part of the cleanup including removing over 670,000 cubic-yards of DDT contaminated sediment and disposed of it in an approved landfill. With studies in the early 2000’s showing the slurry wall and clay cap at the main plant site were not keeping contamination out of the river, the EPA and the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality launched a remedial investigation and feasibility study at the main plant site, the result was the soil and the groundwater were contaminated.

Later in June 2006 a selected remediation project would include a comprehensive cleanup of the main plant site and a residential soil cleanup. The residential soil cleanup would see the EPA move 50,000 tons of contaminated soil to an off-site landfill. In October 2022 the EPA started a new cleanup phase that’s going to excavate 100,000 tons of contaminated soil from the southern part of the old site and trucked to an off-site landfill.

Air is still contaminated 40 years after the Michigan Chemical plant disaster in St. Louis, Michigan

Former Burn Area

Velsicol Burn Pit, Michigan

The 5 acre site is a former burn area where Velsicol Chemical Plant, formerly Michigan Chemical Corporation, used to burn their toxic industrial waste products and pesticides from 1956 – 1970, which is now located in an out-of-bounds area in the Hidden Oaks gulf course (there’s more than oaks hidden here), the pesticides and chemicals used to maintain golf course greens likely doesn’t make the old burn pit any safer or better for the environment and the people wandering around it.

The industrial waste and pesticides that were burned here were then found to have contaminated surface soil and groundwater, according to the EPA there are 25 hazardous chemicals buried on the small parcel, including DDT, benzene, mercury, magnesium and lead. Approximately 2,000-3,000 gallons of hazardous material was dumped in the burn area, the site was first proposed in 1982 to be added to the National Priorities List by the EPA until Velsicol removed 68,000 cubic yards of contaminated soil and because of that action the proposal to add the site to the NPL was cancelled.

More soil and groundwater contamination was discovered in 2006, the EPA and the state of Michigan re-proposed the addition of the site to the NPL, in March 2010 the site was added to the NPL which made federal funding and analysis. There are also 150,000 gallons of something called a non-aqueous phase liquid, or DNAPL, on the property, the EPA plan was to use an in-place thermal treatment system to clean out the 1.4 acres of soil contamination. As of 2024 the EPA had begun startup procedures for the in-place thermal treatment system, the entire remediation is expected to take 2 years and cost $30 million.

Courtesy of Michigan Public NPR

Velsicol Plant,

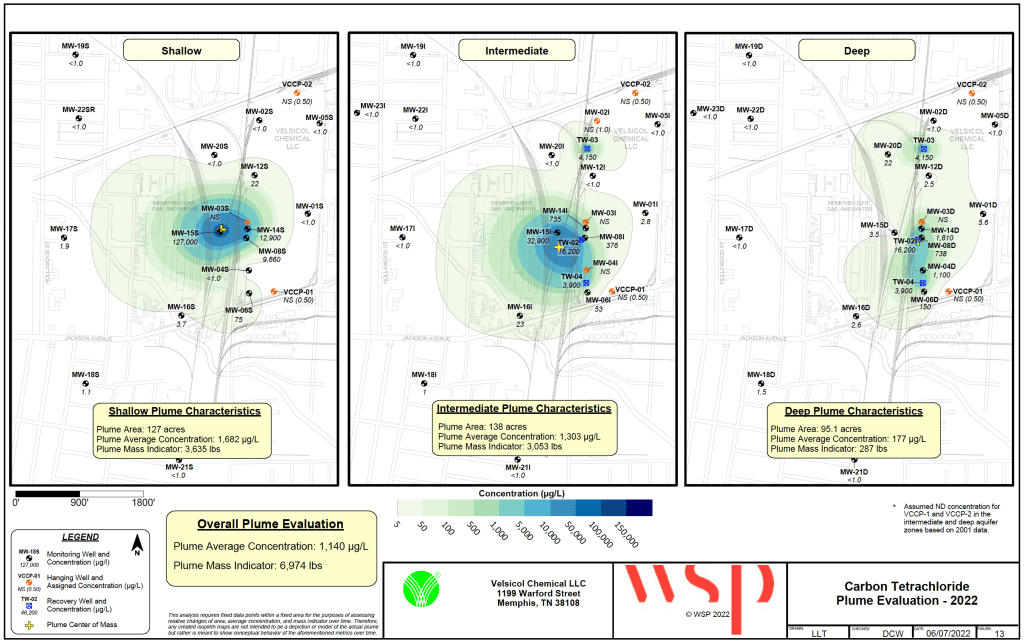

North Memphis, Tennessee

Velsicol who is a legacy polluter, proposed to give the state of Tennessee its 83 acre North Memphis site as an environmental response trust, manufactured chemicals for pesticides so powerful a spray could kill a flying insect before it hit the ground, they were also a large producer of products like chlordane, a man-made substance which was banned by the EPA in 1988 due to its cancer risk. The Wolf River still carries the legacy of the North Memphis plant lives in the depths of the river and the shallow layers above the Memphis Sands Aquifer where sediment contains hazardous industrial chemicals that do not dissolve in water. The fish in Wolf River absorb the chlordane as they swim through the water contaminated with the chemical, which doesn’t break down easily. If someone were to eat the tainted fish they could experience tremors, convulsions or even death, which isn’t very surprising because chlordane was a byproduct of nerve agent used by the US Army in WWII and commercial use starting in 1945.

In 1963 there were nearly 12 million dead fish that were bleeding from their mouths that washed up on the banks of the Mississippi River, south of Memphis, an investigation revealed that Velsicol Chemical was the primary source of the endrin pollution that killed the fish. In the 1960’s the city of Memphis dredged Cyprus Creek to straighten it out and to prevent flooding, while dumping the dredged material in people’s backyards along the creek.

Even though Velsicol plants across the country have become Superfund sites, this site is allowed to operate with a state-sanctioned permit that allows the company to store, treat and dispose of hazardous chemicals, causes they’ve done that so well over the decades. The permit for Velsicol Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), was set to expire in 2024, with the permit Velsicol was allowed to store and distribute chemicals like Hexachlorocyclopentadiene, commonly referred to as Hex, even though they stopped its chemical production in 2012. Hex is a manufactured chemical, not a naturally occurring one, used in flame retardants and pesticides.

There was an explosion of phosgene and chlorine on November 2nd 1955 that killed 2 and wounding 15, there was a leaking railcar in August 1988 that spewed 19,500 gallons of hydrochloric acid into the air, misting workers and residents while spilling into the ground. There was a tank that exploded in February 2001, containing 45,000 gallons of dicyclopentadiene (DCPD) that caused a fire exposing workers, also in 2001 utility workers were exposed to pesticides which prompted soil sampling downstream from the Velsicol plant, testing the backyards of 129 homes along the creek, every single soil sample showed dangerous levels of the carcinogenic pesticide dieldrin, up to 15 times over the maximum threshold. Velsicol was forced to remediate the contamination in response, cleaning up 18 of the most heavily contaminated properties along the creek by 2007. Springdale Creek Apartments, at 2510 Jackson Avenue in Memphis was built on the site of a former junkyard that was filled in with the material dredged from the Cypress Creek in the 1960’s, now being designated as a Superfund site from the contamination buried below the apartment building. In 2023 there was soil and vapor sampling done at residences along the creek, indicating contamination still remains in the neighborhood.

In the 1990s Velsicol Memphis plant was the main producer of chlordane in the United States, which was banned for use in America but still allowed to be sold internationally, with this plant continuing to produce 2.5 million pounds of the chemicals chlordane, endrin and heptachlor for global export until 1997. Once the company stopped production later that decade, they later reported a subterranean plume of chemicals that was roughly of the Liberty Bowl stadium, approximately 126 acres in size, which is located in Memphis, the plume contained 80,000 pounds of carbon tetrachloride. Hex can be produced as a byproduct of creating carbon tetrachloride. Velsicol has also been attempting to cleanup Cyprus Creek, with lab tests in 2023 showing contamination exceeding EPA’s limit at the neighboring apartments on Springdale St, where aldrin, endrin and dieldren were found; which are chemicals linked to neurological, reproductive and developmental harm.

As far as pollution in the waterway, Cyprus creek feeds the Wolf River and eventually the Mississippi River, so any pollution or industrial chemical contamination is likely to spread to a large number of people who live on or near these waterways or have private wells that pull from groundwater contaminated from miles away. Velsicol has a network of wells in order to calculate the boundary and weight of the plume, made mostly from carbon tetrachloride; the wells are estimated to remove 2,229 pounds of carbon tetrachloride annually. Even though the plume has reduced from 80,000 pound to 7,000 pounds of carbon tetrachloride, that doesn’t mean the danger is gone even though Velsicol claims the plume is “under control”.

The reality is the plume doesn’t stay in one place, in 2018 the plume spiked to its original size of about 280 acres, before shrinking to its current acreage, with fluctuations like heavy rainfall leading to the plume moving concentrations of the chemical downward. In 2018 the soil sample levels for dieldrin were nearly three times the EPA standard for residential properties. The most frequently found contaminant found at dangerous levels in fish is chlordane, which accumulates in their fatty tissues, posing a risk for people who eat the fish.

Velsicol Dump Sites

Hardeman County Dump

Toone, Tennessee

Hayden Chemical Company would use the site as a landfill from 1964 – 1973, disposing of approximately 130,000 drums of plant waste. In 1979 the EPA identified groundwater contamination in private wells prompting the city of Toone to connect businesses and residences to the public water supply, following the contamination in 1983 the site was added to the Superfund NPL.

There was a 242 acre parcel in Toone, Tennessee where Velsicol took their chemical waste to be disposed of in a 27 acre burial site on that parcel, dumping pesticide manufacturing waste and volatile organic compounds (VOC’s) from 1964 – 1973. Approximately 300,000 drums of chemical waste were dumped, at 55 gallons per drum estimate that’s over 16 million gallons of waste from pesticide production.

The EPA found contamination in 1980, they found pesticides and heavy metals in the surface soil, groundwater and pond sediments at the landfill, with an estimated 10,000 people living within 3 miles of the site and in a heavy area of concern. The same year the EPA took emergency action trying to stop the movement of contaminants from the site, installing a chain link fence and beginning an on-site waste monitoring program. The following year in 1981, the EPA started to remove surface level contamination.

With investigations of the site there was soil contamination found at 60 to 70 feet below the base of the landfill and an estimated 3.6 million cubic yards of soil underlying the wastes were contaminated, even private drinking wells in the nearby area were impacted by the groundwater contamination, a municipal water supply connection was then provided. There is a 1,700 acre groundwater plume that comes from the site and spreads to down gradient streams and wetlands; carbon tetrachloride, which is the primary contaminant in groundwater, has a maximum contaminant level of 5 micrograms per liter, the measured concentrations over a large port of the plume exceeds 5,000 micrograms per liter and they’ve even recorded concentrations as high as 64,000 micrograms per liter.

North Hollywood Dump

Memphis, Tennessee

From the 1930’s til 1963 the site was used as a municipal landfill. In total the property was 171 acres, 70 acres of that was for the landfill, a 35 acre abandoned dredge pond, two former surface water impoundments for another 13.5 acres and a forested buffer area. The waste was generated by the production of sodium hydrochloride, Velsicol would buy Hayden Chemical Company and continue dumping chemical and industrial waste at the dump on the 27 acre landfill, other industrial companies would use the landfill over the years too.

Health Consultation- Abandoned Dredge Pond

Prepared by Tennessee Department of Health

Sterling vs. Velsicol Chemical Corp.

People who lived near a Velsicol dump site, referred to by the company as a farm, filed a lawsuit against Velsicol in 1986, with attorneys for the plaintiffs arguing Velsicol may have pocketed from $23 to $63 million from not paying for proper chemical disposal.

“Velsicol has taken the position that without the farm, the Memphis plant would close,” reads the court case. “Thus, the Court believes that it would be appropriate to deprive Velsicol of a reasonable part of the profit it made by improperly disposing of those chemical wastes to keep that plant open.”

The lawsuit initially saw Velsicol held liable for millions of dollars in damages, that was overturned on appeal.

District of DC vs. Velsicol Chemical LLC

Introduction

No later than 1959, Velsicol was given private lab studies that chlordane caused birth defects in animals and by the 70’s knew that tests linked it to liver cancer. Research in the late 80’s indicated the Anacostia and Potomac Rivers had triple the amount of chlordane recommended for human consumption, the levels were high enough in 1989 that the city warned against eating carp, catfish or eel caught in the river. As of 2016, about 55% of D.C. waterways were “impaired” under water quality standards for chlordane levels.

- The District’s waterways and natural resources have been and continue to be contaminated by a toxic, cancer-causing chemical named chlordane. This contamination is directly traceable to Velsicol, the sole manufacturer of technical chlordane, which was one of the most widely used pesticides in this country until it was banned in 1988 by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) because of the threat it poses to human health. However, decades before that ban, Velsicol knew chlordane was a persistent toxin that would leech into waterways, disperse in the environment, and threaten human health. Indeed, by the early 1970’s, Velsicol’s internal studies had confirmed that the chemical caused cancer. But rather than halt its sales and share this information with the public or with regulators, Velsicol embarked on a years-long campaign of misinformation and deception to prolong reaping the financial rewards of selling its chlordane products, including throughout the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia. This campaign included targeted advertisements for dangerous household use of chlordane and resisting the EPA’s efforts to ban continued sales of chlordane long after Velsicol knew about the chemical’s toxic effects.

- Velsicol’s efforts worked. Chlordane was one of the most common pesticides in the United States and accounted for more than two-thirds of Velsicol’s annual sales. By the time the EPA finally banned chlordane over Velsicol’s objections, more than 30 million homes and commercial structures had been treated with this toxic and persistent chemical. The year after sales fully stopped, District residents were warned not to eat certain fish caught from the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers because of continuing chlordane contamination. Chlordane continues to widely contaminate the District’s natural resources, including its waters. Addressing Velsicol’s contamination of the District with chlordane has cost, and will continue to cost District taxpayers tens of millions of dollars.

Leif Skoogfors/Corbis via Getty Images)

Courtesy of Business Insider

Centralia Coal Mine Fire

Centralia, Pennsylvania

The town was formed in 1811 and was originally known as Bull’s Head, later being known at Centreville before being officially incorporated as Centralia Borough in 1866, founded by mining engineer, Alexander Rae. Construction in 1854 of the Mine Run Railroad turned this town into a mining hub, connecting the community to the rest of the region and transporting coal out of the valley. By 1890, the town was home to more than 2,761 people according to the US Census, it covers roughly 155 acres and is where 1,100-1,200 people used to live prior to the 1962 mine fire starting. At its peak the town was big enough to host 5 hotels, a bank, two theaters, seven churches, 27 saloons, a post office as well as 14 general and grocery stores at its peak around 1900, there were also 14 active coal mines.

Mining for anthracite coal began in 1942 with the Centralia Colliery opening in 1862 but had been inactive since the 1930’s. Anthracite coal is what makes this area special; its high carbon content (86-97%), hardness, high energy density and the fewest impurities is what makes this type of coal highly sought after, it’s also slow burning and clean with very little smoke or particulate emissions compared to other coal.

Prior to Memorial Day of 1962 the town was preparing for the celebrations by some local volunteer fireman burning some garbage on May 25th, as was the norm. At the end of the blaze they put out all the visible flames, unknowingly allowing the fire to spread into the coal seam below, for a few days after the fire- flames would continue to crop up. Random fires would continue to spring up as the coals burned, even without a visible fire the smoke and stench of burning coal permeated the town. Later it would be discovered there was a 15 foot wide hole that was several feet deep that was never filled with flame-retardant material, the fire has been able to spread through the honeycomb of coal mines ever since.

The fire that started as just the regular burning of the town’s trash, has spread to the point of devouring an area the size of 35 football fields. Some of the gas exhaust vents were measuring between 456°C (852.8°F) and 540 °C (1004°F) in 2005 and the fire below ground was recorded to be moving rapidly at a rate of 20–22 meters (65-72 feet) per year. A decade later in 2015 the average annual temperature of surface exhaust fences is roughly ~65 °C (149°F) and the spread of the fire underground is nearly unperceivable. There was an attempt to stop the spread of the fire in 1969 by creating an underground barrier using the remains of burnt coal to stop the spread of fire, it failed to do so. Other attempts had failed including pumping water into the shafts which left the town at risk for steam explosions, the town also tried to dump clay and slurry to stop the fire from spreading, that failed too. The cost to dig up part of the town and the remaining coal could cost approximately $400 million according to some experts, the United States Office of Surface Mining (OSM) estimated in 1983 that it could cost $663 million to extinguish the fire.

The local gas station was owned by John Coddington, he noticed in November of 1979 that there was steam rising from the lot next to his gas station, he had some concerns because he had four underground tanks that were holding a total of 9,000 gallons of gasoline. Not long after that, just a month later in December his basement floor was warm to the touch and he saw steam coming from the floor, the temperature measured 136 degrees Fahrenheit, officials began to monitor the temperature of the gas- the heat was steadily rising so the Pennsylvania Police fire marshall ordered the station to shut down. John then had to pump all the gas out and fill the tanks with water to prevent an explosion, the Coddington Gas and Service Station was demolished in 1981.

There was even a kid who fell into a hole on Valentine’s Day in 1981 that was opening up in the backyard of his grandmother, a 150 foot fissure that once served as a mine shaft opened up below him. Luckily for 12 year-old Todd Domboski his cousin, Eric Wolfgang, came to his rescue, pulling him from the hole, when the ground gave way. Todd fell about 6 feet and he had grabbed onto a tree root as the ground beneath him disappeared, likely being the only thing saving Todd, thankfully he was not injured in the fall. Town officials later measured the heat inside the hole at 350 degrees Fahrenheit.

It’s currently been burning for the last 50 years and is estimated that it will continue to burn for at least another 100 years into the future and possibly for 250 years, for the next several generations to deal with and live around. It could burn across an 8-mile stretch that encompasses 3,700 acres before it runs out of the coal fueling the mine-fire. The few people that lived there as of 2012 had no zip code as the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) revoked the zip code in September 2003, then the 10 remaining people had no mail service. As of January 2013 there were 5 remaining residents. As the fire continues to burn and emit sulfur and carbon monoxide into the atmosphere above giving off a thick poisonous air for the remaining residents to struggle through.

The government started to help in 1981, assisting families to relocate after attempts to put out the fire failed, to the tune of $3.5 million, according to The New York Times. Then in 1983 the government spent $42 million to buy residents homes and relocate residents even though some refused to leave, with 10 residents not taking the buyout. The government has tried to obtain the remaining properties through eminent domain, the few residents trying to stay put were trying to fight the federal government. By the end of the 1980’s over 500 structures had been demolished and more than a thousand people had moved from the town. In 1992, the state of Pennsylvania ordered the remaining residents out but gave them one last chance for the buyout program, the state issued an Eminent Domain fIn the 1990’s a handful of residents who had their homes seized filed a federal lawsuit that accused the government of wanting the towns coal and claimed the parts of town where they lived were safe. The residents won and were allowed to stay as long as they live and also each received a cash payout of $349,500, but they could not sell or give away the property, once they pass the state will seize the land and demolish the remaining buildings.

As of 2008 the fire underground spans over 350 acres and is burning 300-400 feet below the surface, reaching a temperature of up to 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit. A geologist in 2012 with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection said that the fire that’s existed underground for decades may have gone deeper underground, it still poses a threat because it has the potential to open new pathways for deadly gases to reach the remaining homes. The residents who stay behind say that’s nonsense because they’ve lived in their homes for decades without incident. According to the U.S. census in 2020, it showed only 5 residents still living in what’s left of the mining town.

The town’s eerie look was even part of the inspiration the French-Canadian horror franchise, “Silent Hill”. It was also known for what was called “Graffiti Highway”, a stretch of Pennsylvania Route 61 that was damaged by the underground fire and led it to be a canvas for graffiti artists, was closed indefinitely in 1993 and it was later covered with dirt in 2020 to deter tourists from visiting.

“Even the dead cannot rest in peace,” wrote Greg Walter for People in 1981. “Graves in the town’s two cemeteries are believed to have dropped into the abyss of fire that rages below them.”

Link to Fire Location Map

Link to Centralia Fire

Potential Spread Map

Centralia Mine Fire Mercury Study

Final Report – March 2008

Courtesy Business Insider

Courtesy of R. Miller/FlickrCentralia

Leif Skoogfors/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

Courtesy Business Insider

Courtesy Historic Mysteries

Courtesy Business Insider

Courtesy Historic Mysteries

Courtesy Business Insider

Courtesy Business Insider

Courtesy Historic Mysteries

Courtesy Changes in Longitude

Courtesy of Treehugger

Courtesy Business Insider

Courtesy Business Insider

Bettmann/Getty Images